Key Points

In our June edition of the IndonesiaPulse, we assess our short-term outlook for the Indonesian rupiah, given its recent weakness and ongoing global uncertainty. We also delve into how the government’s downstreaming policy and a broader plan to establish an end-to-end EV industry will strengthen Indonesia’s external resilience, improving the long-term appeal of the rupiah.

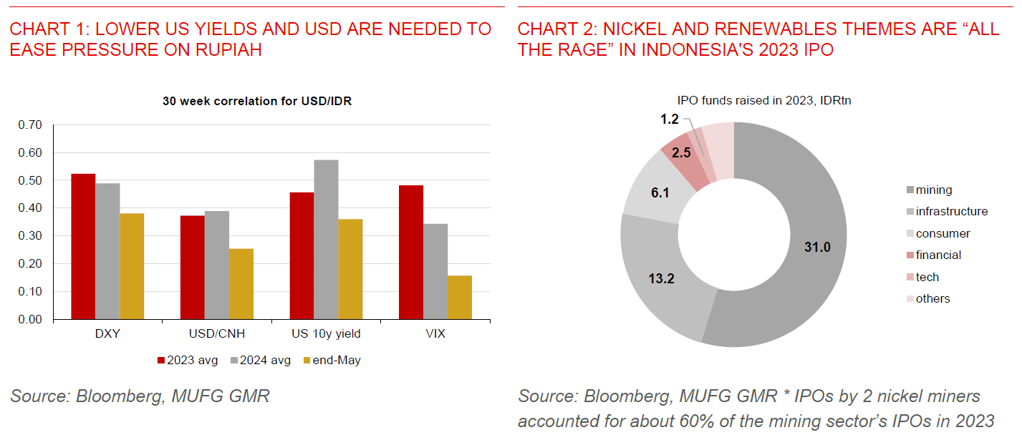

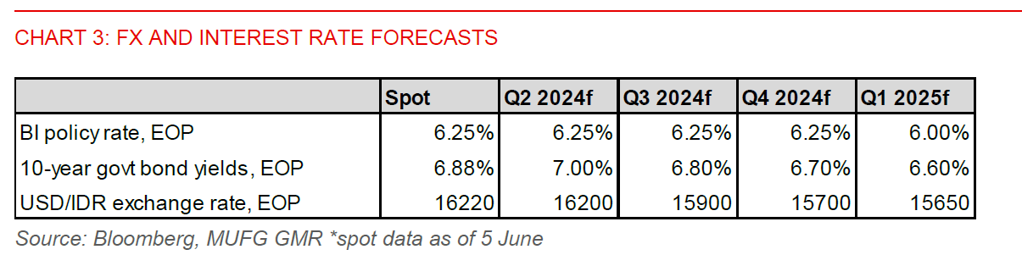

- We forecast USD/IDR to consolidate at around 16,000 in 3 months before falling modestly to 15,650 by early 2025.

- Our base case is for US interest rates to trend lower in the next 6-12 months, the US dollar to weaken, BI to react swiftly to currency weakness via its mix of monetary policy tools, and global financial market uncertainty to ease.

- Beyond the short-term headwinds, there’s scope for rupiah stability, given an improvement in the long-term appeal of the currency driven by the nickel export ban in 2020. Indeed, the nickel downstreaming policy has made significant positive contributions to the country’s trade balance and foreign direct investment (FDI) in recent years. Trade surplus in the basic metal sector has risen four-folds to US$14.5bn (1.1% of GDP) in 2023 vs. US$3.5bn (0.3% of GDP) in 2020, while the sector also added US$10.7bn (0.8% of GDP) to annual realised FDI inflows in 2023 compared to 2019 levels.

- With the global EV transition set to roll on, these positive contributions will likely only get bigger, which could in turn strengthen Indonesia’s external resilience and foster rupiah stability. We estimate the export of nickel related products could rise to 3% of GDP by 2030, from 2.4% of GDP in 2023. Moreover, the nickel downstreaming policy is likely to continue under incoming President Prabowo, as he has pledged to continue the major economic policies of outgoing President Jokowi.

- Currently, Indonesia has a grip on the upstream segment of the EV supply chain, driven by its natural advantage in nickel reserves which is accompanied by the nickel export ban. However, a foray into the midstream (EV battery production) and downstream sectors (EV production), currently dominated by China, will be equally crucial. Encouragingly, we have seen policy positives from the Indonesian government, though more needs to be done to speed up EV adoption.

Short-term rupiah headwinds

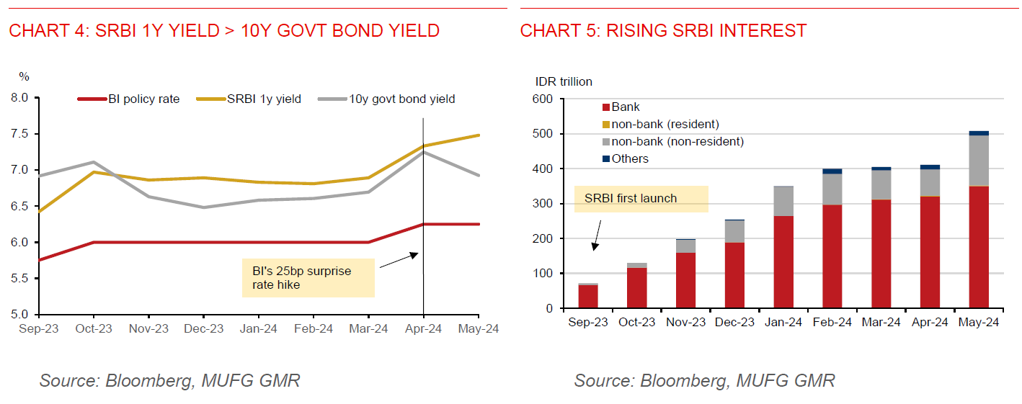

- Bank Indonesia (BI)’s willingness to react swiftly to stem rupiah weakness using a range of instruments should help the rupiah. These instruments include raising the policy rate by 25bps to 6.25% in April, direct FX intervention, and issuing its own rupiah securities (SRBI) at attractive yields of more than 7% (Chart 4). This has helped stabilized the rupiah in May. Notably, the amount of SRBI outstanding jumped IDR97.7tn (US$6.1bn) as of May 21 to IDR508.4tn (US$31.8bn) compared to end-April, marking the largest monthly increase since its inception in September 2023 (Chart 5). The share of foreign holding has also surged to 28.1% in May, up from 18.3% in April.

- However, financial market uncertainty remains high in the short term. This has been driven by a triumvirate of a lack of market clarity on the timing of US rate cuts, geopolitical risks, as well as Indonesia’s own political transition and associated fiscal risks under an impending new government. Year-to-date, the rupiah has depreciated by more than 5% against the US dollar year-to-date, after the rupiah had stabilized in 2023 with a 1% gain. It’s clear that the rupiah still won’t be immune to sudden bouts of global volatility, despite improved domestic macro fundamentals relative to during the 2013 taper tantrum. Our scenario analysis suggests USD/IDR could still spike to 16,600 on a geopolitical shock from the Middle East.

Increased long-term appeal

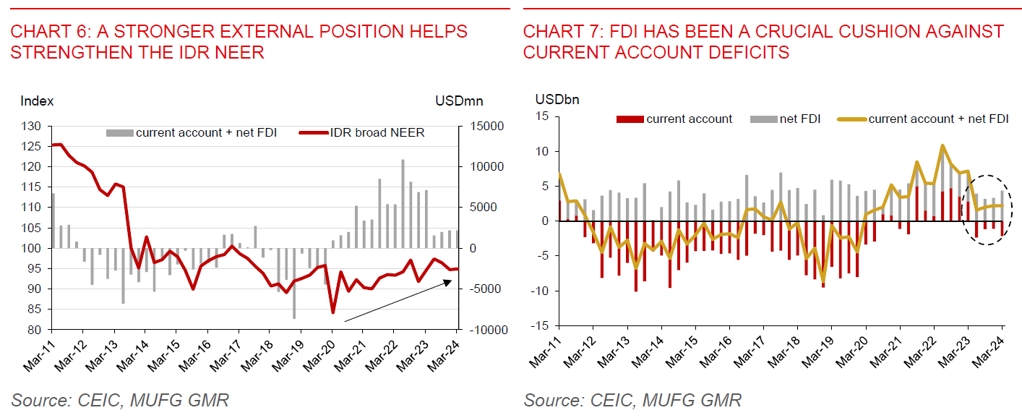

- However, from a medium- to long-term perspective, Indonesia’s economy will likely need to generate sustainable current account surplus and attract more FDI inflows to keep the rupiah relatively stable, in our view. Indeed, an improvement in the trade balance since 2021, along with net FDI inflows, have helped the IDR broad nominal effective exchange rate to appreciate (Chart 6). Also, net FDI inflows since Q2 2023 have helped provided an offset against renewed current account deficits (Chart 7).

- Encouragingly, our analysis suggests a fundamental shift in the medium- to long-term rupiah outlook is underway. A key driver is the nickel downstreaming policy implemented by President Jokowi since 2020, along with the associated plan to construct an end-to-end electric vehicle (EV) supply chain in the country. While there is a political leadership transition going on this year, we believe the downstreaming policy is likely to continue in the coming years, given the benefits it has reaped and will provide for the economy. Moreover, incoming President Prabowo Subianto has pledged to continue the major economic policies of outgoing President Jokowi, which include the mineral downstreaming policy, among others.

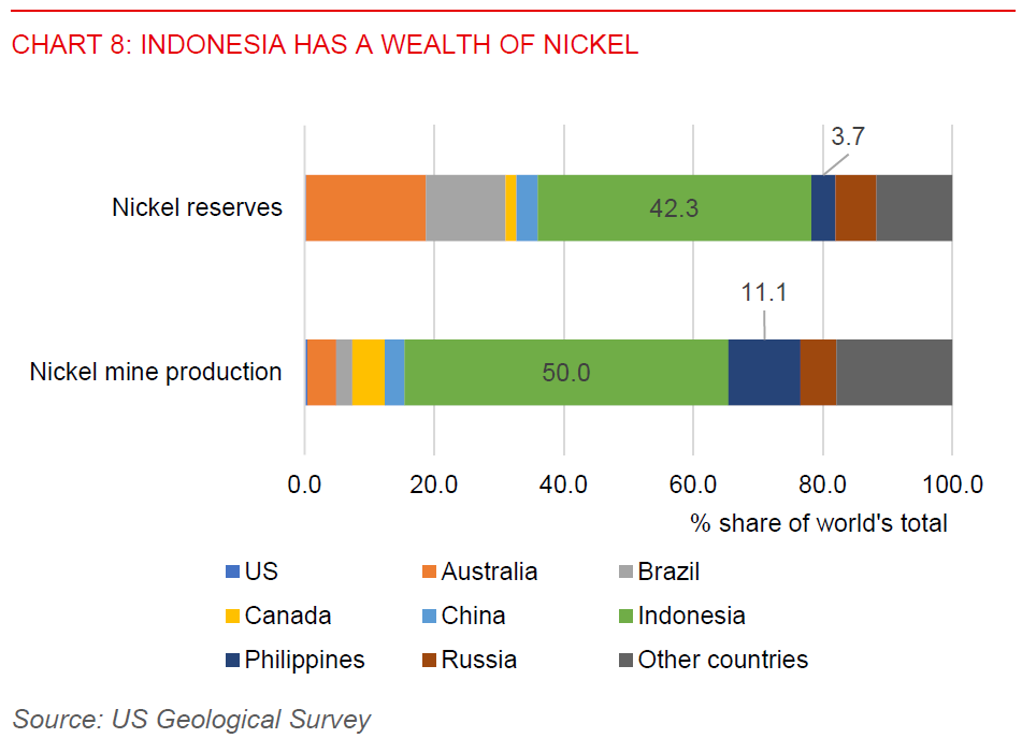

- The nickel downstreaming policy entails Indonesia leveraging its natural advantage as the world’s largest nickel producer to firmly embed itself as a critical player in the upstream segment of the electric vehicle (EV) supply chain. Nickel is a critical ingredient in nickel-based EV battery production. With the country holding more than 40% of the world’s nickel reserves and accounting for half of the global nickel output, according to data from the US geological survey, Indonesia has made itself an indispensable partner in the global transition towards EVs through banning the export of raw nickel in 2020 (Chart 8). This will help capture a higher economic value for its nickel resource, as opposed to exporting low-value raw nickel.

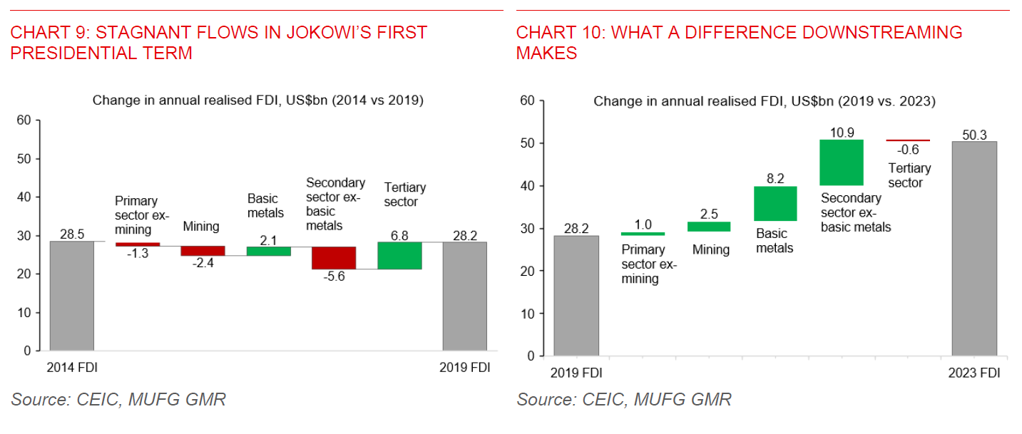

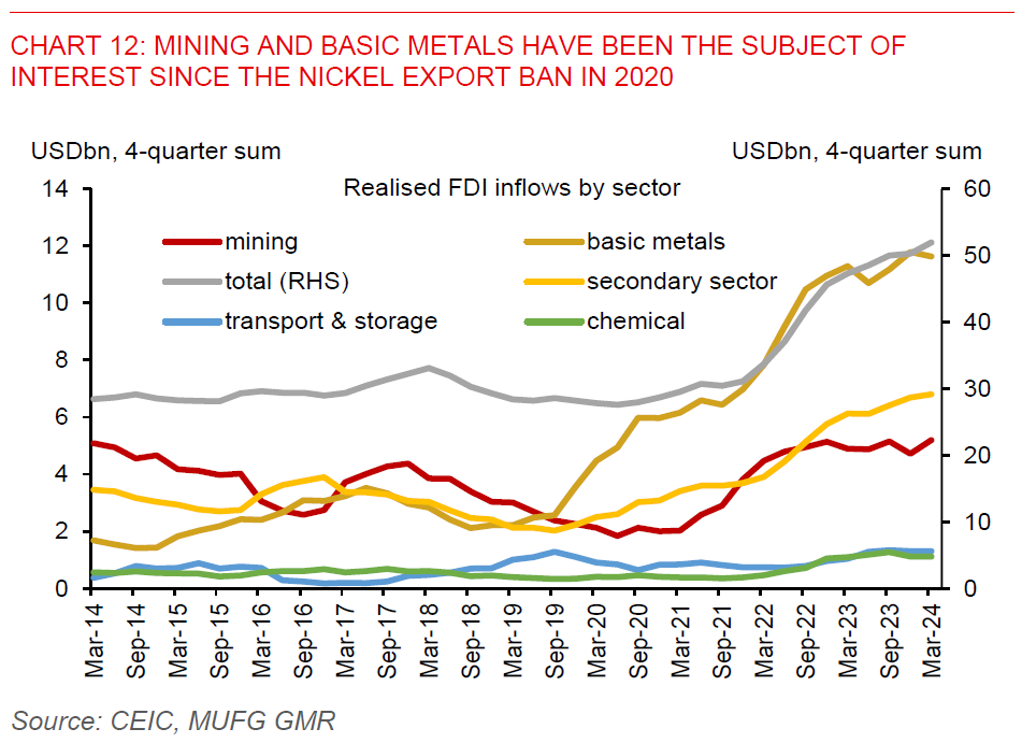

- Our analysis shows that the nickel export ban has contributed positively to the goods trade balance and foreign investment inflows, validating the government’s plans to impose the ban. Indeed, the ban has forced global manufacturers to invest and set up nickel refining facilities in Indonesia, partly driving the increase in FDI. Since the nickel export ban in January 2020, annual realised FDI inflows were US$22.1bn more in 2023, of which mining (US$2.5bn) and basic metal (US$8.2bn) contributed to nearly half of that increase (Chart 10). Prior to this, annual FDI flows were stagnant during President Jokowi’s first 5-year term in office (Chart 9). Indonesia received US$28.2bn worth of FDI in 2019, a US$320mn decline from the US$28.5bn worth of FDI inflows in 2014. FDI received by the mining sector in 2019 was also smaller by US$2.4bn versus 2014, offsetting the modest US$2.1bn increase in the basic metal industry.

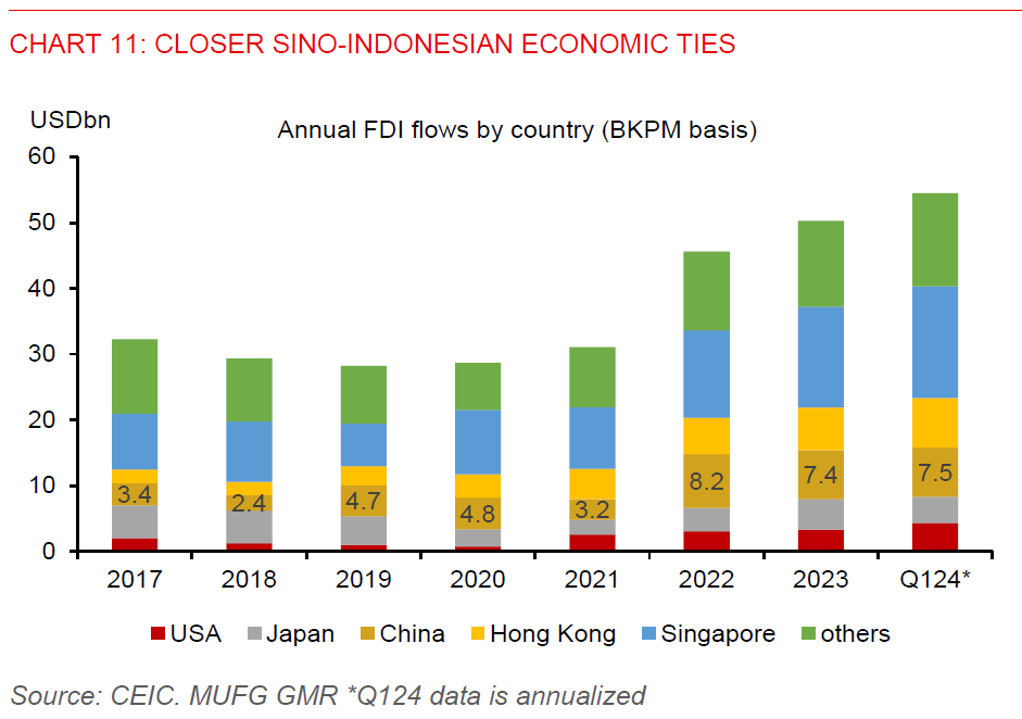

- There has also been a notable rise in Chinese investment in the basic metal sector, particularly nickel smelting, following the export ban. Indeed, China lacks nickel reserves, yet it is a major downstream consumer of nickel for producing stainless steel and lithium-ion batteries for EVs. Indonesia’s FDI inflows from China more than doubled to US$5.9bn on average per year during 2020-2023, despite the pandemic, from just US$2.4bn on average per year in the prior five years during 2015-2019 (Chart 11).

- Latest data also showed continued momentum in FDI inflows. Realized FDI rose 14%yoy in Q1 to US$13.6bn. By sector, Indonesia’s mining and basic metal sectors combined received US$4.2bn worth of FDI or about one-third of total FDI received. The chemical sector received US$1.1bn worth of FDI (7.9% of total FDI), while the transport and communications sector received US$1.2bn (8.7%). By destination, China and Hong Kong contributed to two-thirds of the FDI increase in Q1, at 40% and 26% respectively.

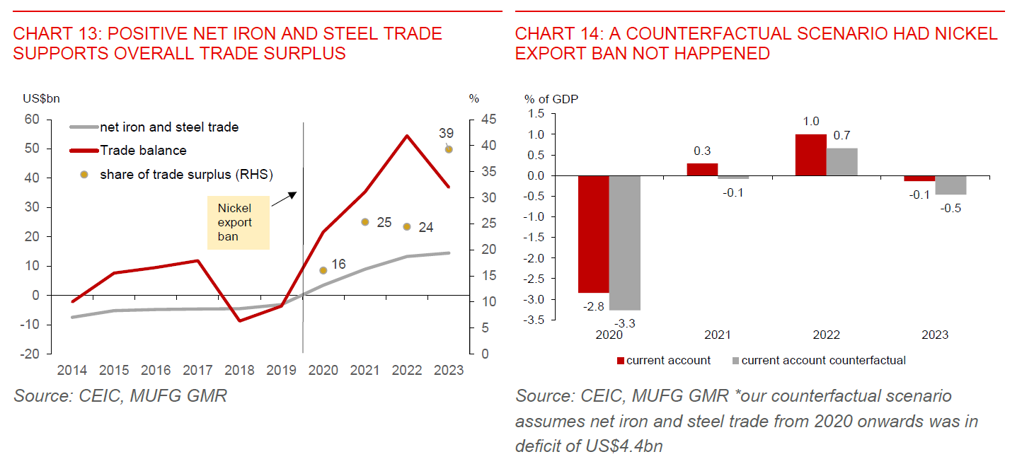

- In addition, the basic metal sector (notably iron and steel) contributed about 40% (US$14.5bn) of the overall trade surplus in 2023, up from just 16% (US$3.5bn) in 2020 during the first year of the nickel export ban (Chart 13). Prior to the export ban, iron and steel trade balance was in deficits, averaging US$4.4bn per year during 2015-2019. Had the iron and steel trade balance in 2023 stayed at the 2015-2019 average deficit of US$4.4bn, Indonesia’s current account would have been much worse, at -0.5% of GDP vs. the actual outcome of -0.1% of GDP (Chart 14). The current account would have also flipped into deficit in 2021, instead of posting a modest surplus.

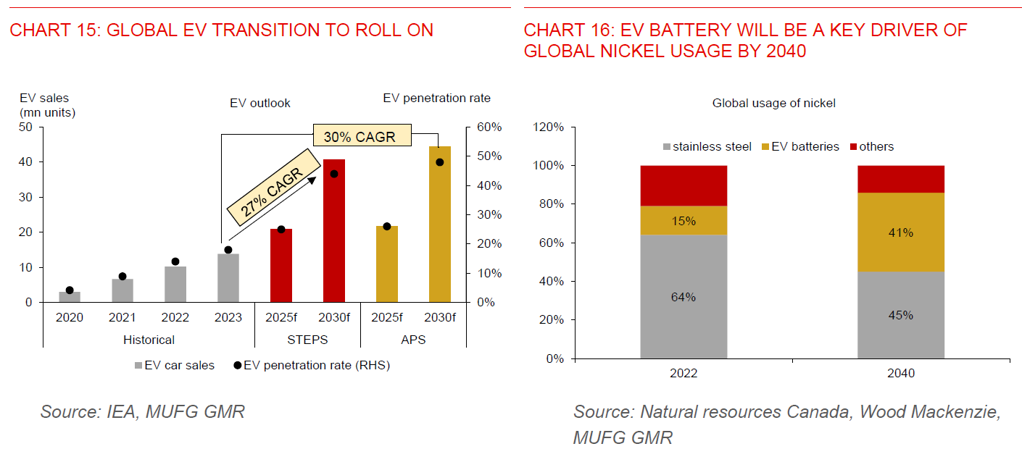

- With the global EV sales expected to grow at a CAGR of 27% to reach more than 40mn units by 2030, there will be increased demand for EV batteries and nickel (Chart 15). Notably, EV battery will be a crucial growth driver of nickel demand in the years ahead. Currently, nickel has mainly been used to produce stainless steel, with only 15% of nickel production going to EV battery manufacturing. But by 2040, it is estimated that the share of nickel for EV battery production will rise to 41% (Chart 16). As such, Indonesia’s rising nickel exports trend is likely to persist. We estimate that nickel downstreaming products could increase to US$56bn (3% of GDP) by 2030, from around US$33.5bn (2.4% of GDP) in 2023, representing a 0.6ppt increase as a share of GDP.

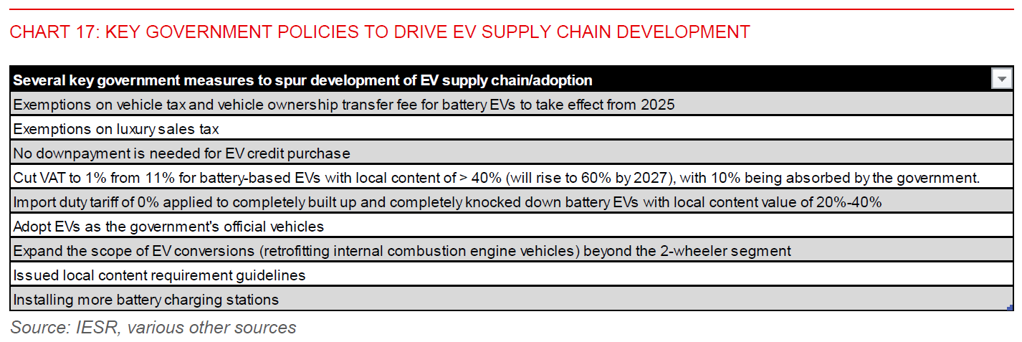

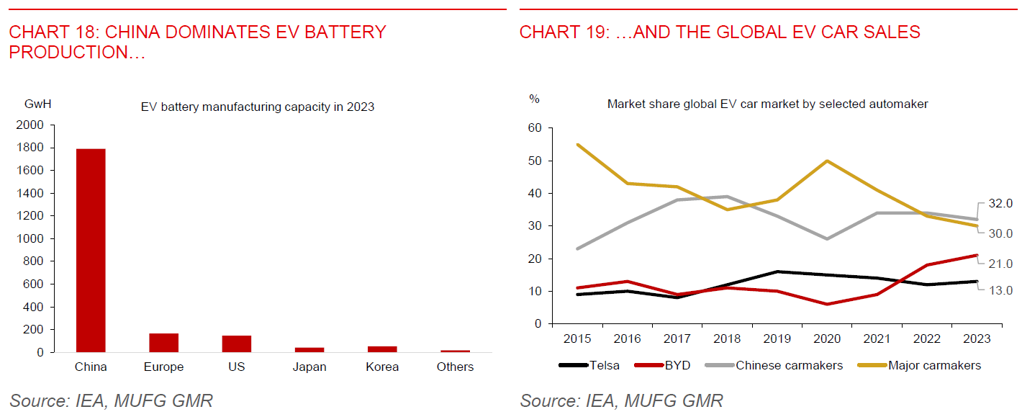

- The government is also providing incentives to help drive the development of the midstream and downstream segments of the EV supply chain, which will in turn boost EV related investment (Chart 17). For now, Indonesia’s midstream (such as EV battery production) and downstream sectors (such as EV production) are still lagging global players, although the first EV battery production is expected to come online in June. Four state-owned enterprises (PLN, Pertamina, Antam, and Inalum) have formed the Indonesia Battery Corporation (IBC) in 2021 to support the development of EV battery cells. Currently, China dominates the global EV supply chain, holding about 80% of global EV battery manufacturing capacity (Chart 18) and one-third of global EV market share (Chart 19). So, there’s quite a lot of catch-up to do for Indonesia in the midstream and downstream EV segments.

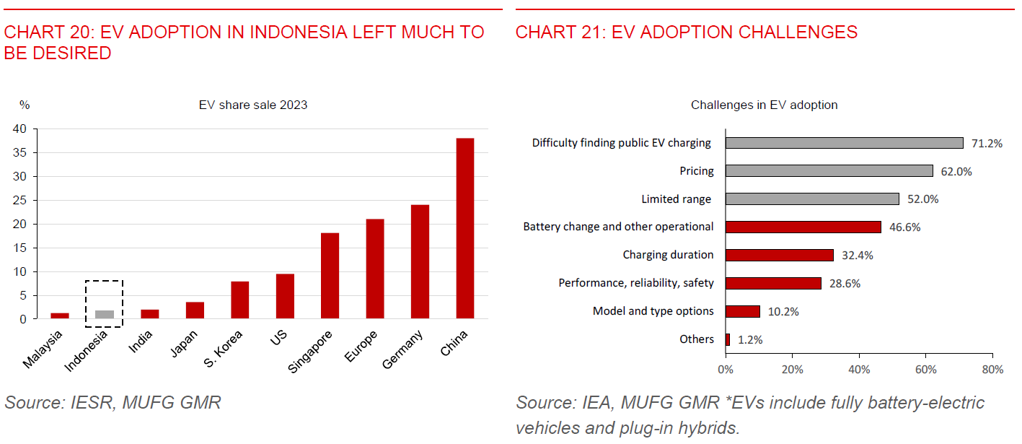

- EV adoption has also gathered pace in recent years, jumping to 17,000 units of 4-wheelers, from less than 100 in 2019. It has benefitted from the government cutting the value-added tax to 1% from 11% for battery based EVs with local content of more than 40% in 2023, with 10% VAT being absorbed by the government. But EV penetration is still relatively low in the country (Chart 20), constraining Indonesia’s ability to woo more EV makers to set up production facilities in the country. Top 3 challenges in faster EV adoption include difficulty in finding public EV charging stations, EV pricing, and limited travelling range (Chart 21). Notably, even with a 10% discount incentive for purchasing an EV, a mid-class EV are still priced above IDR300mn. The market share of four-wheelers priced above IDR300mn was only about 1% in Indonesia.