-

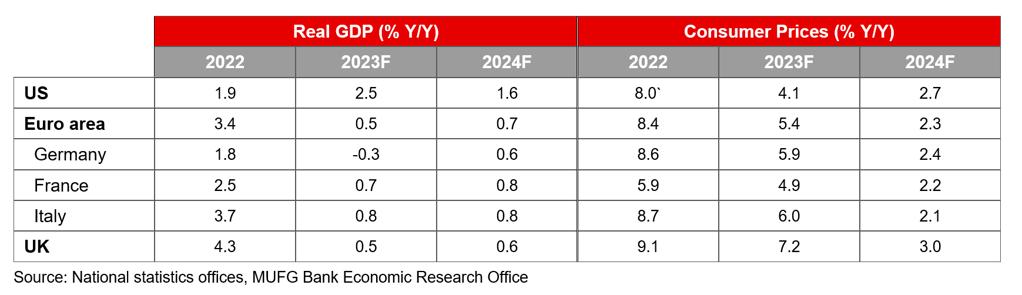

The US has significantly outperformed the European economy in 2023, driven by resilient consumer spending and fiscal policy support. Unlike in the US, nobody is talking about ‘landings’, soft or otherwise, in the euro area or UK because the neither economy has managed to take off in the first place.

-

We do not expect the gap to widen further in 2024. In our base scenario, the US economy is set to undergo a cyclical slowdown while activity in the euro area and UK is set to accelerate slightly as households’ spending power recovers. We look for growth of 0.7% in the euro area and 0.6% in the UK.

-

That said, there is growing recognition that EU strategy needs to address competitive imbalances as the US pursues a more active industrial policy. The response so far has centred around leveraging pandemic/energy crisis-related tools. Without an acute crisis, further changes are unlikely to be quick and we are not holding our breath for meaningful reform on the EU side.

-

The inflation situation either side of the Atlantic has been remarkably similar despite different backdrops in terms of demand, and the disinflation process should continue. On monetary policy, the ECB and BoE have closely followed the Fed, but the US economy looks better placed to absorb interest rate rises. For this reason, risks to our Europe forecasts remain tilted to the downside.

US outperformance is set to fade in 2024

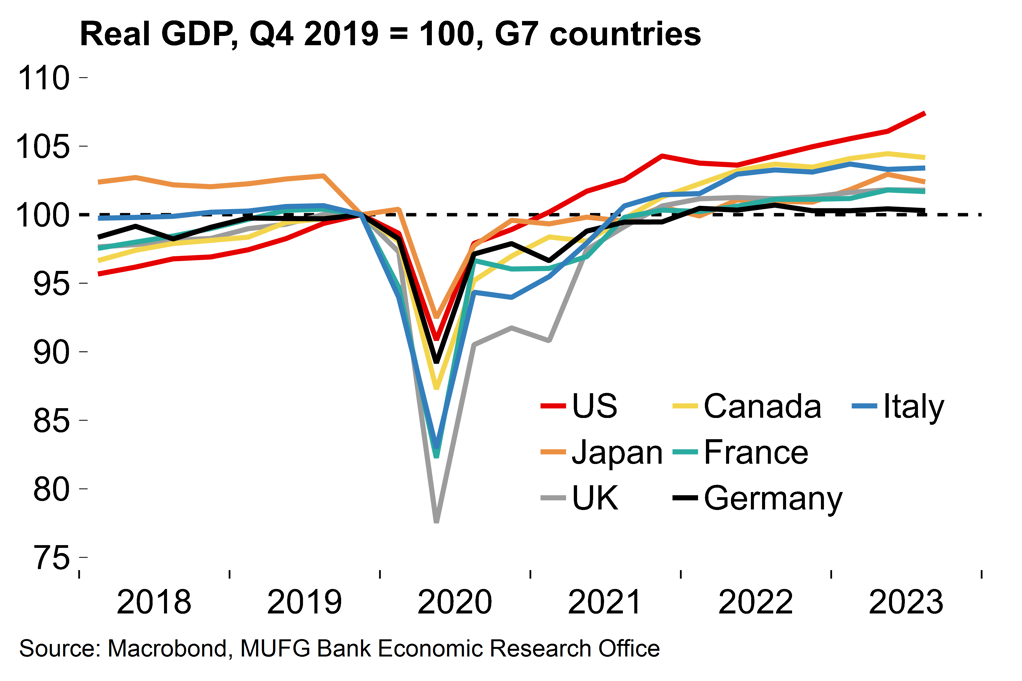

A key theme of 2023 has been the outperformance of the US economy – both relative to expectations at the start of the year but also when compared to Europe (Chart 1).

Chart 1: US growth has outpaced other G7 economies in recent years

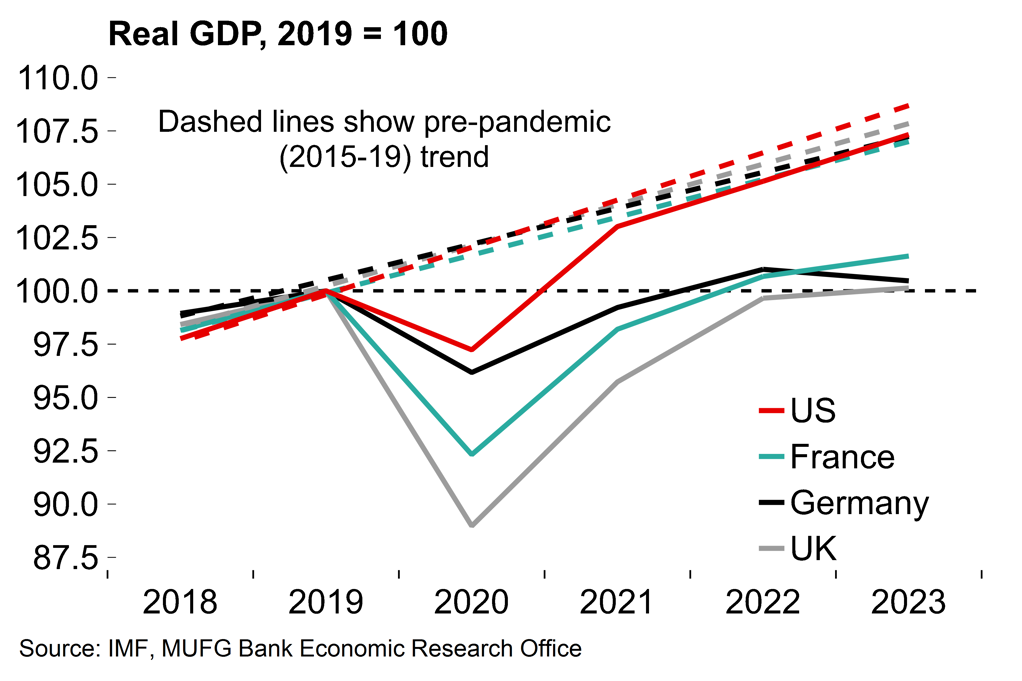

Chart 2: Unlike Europe, the US does not seem to have suffered significant scarring from the pandemic

Unlike with the US, nobody is talking about ‘landings’ for the euro area or the UK, soft or otherwise, simply because neither economy has managed to take off in the first place. The US economy has expanded by 3.5% since the start of 2022. The UK has grown by just 0.6% over the same period. The euro area as a whole has eked out slightly more respectable growth of 1.8%, supported by better figures from Southern members, but Germany, the largest economy, has shrunk by 0.1% since Q1 2022. While the US has been performing strongly, Europe has been stagnating.

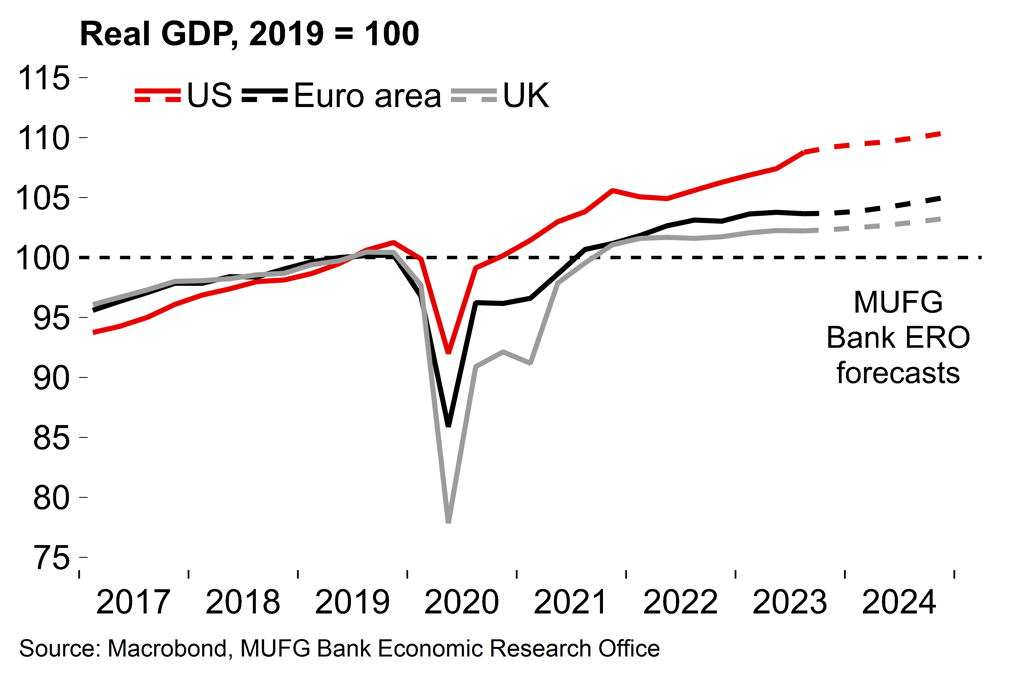

While we’re doubtful that Europe will be able to close the gap, we do expect the narrative of divergence to fade through 2024 with European growth accelerating slightly and the US economy to experience a cyclical slowdown as some tailwinds fade.

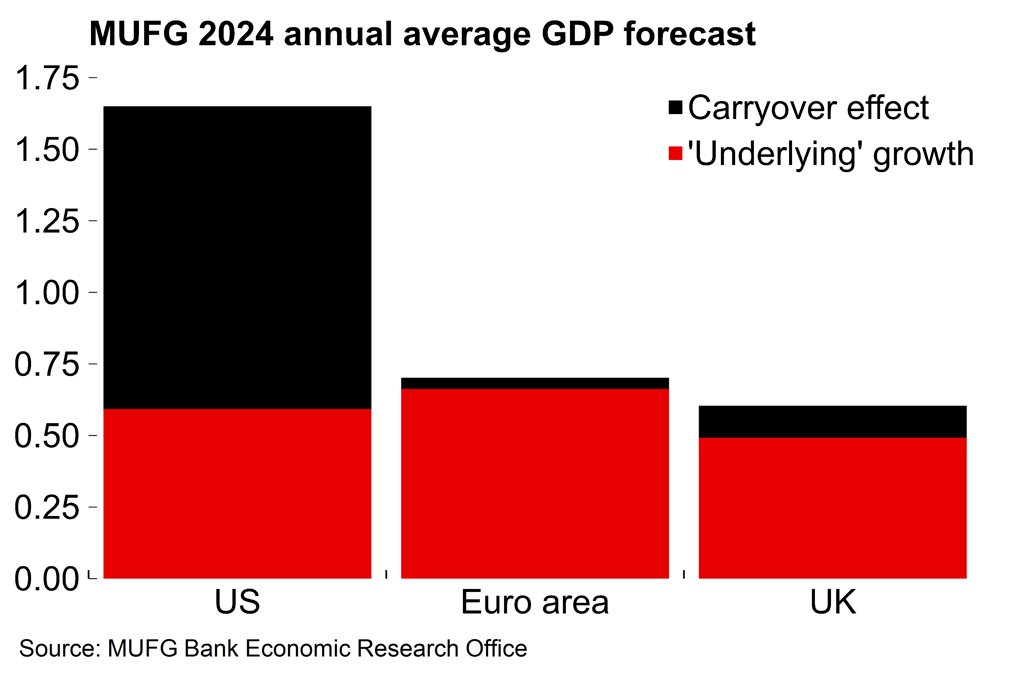

Chart 3: US headline growth in 2024 may be higher, but that reflects strong momentum in H2 2023

Chart 4: We expect US GDP divergence to end (but it’s a tough ask for Europe to catch back up)

We are slightly above consensus on annual average GDP growth for both the euro area (0.7%) and UK (0.6%) in 2024, and we expect US growth of 1.6%. It’s important to unpick the carryover effect (or overhang of growth dynamics in 2023) from these figures after the recent divergence between the European and US economies. Essentially, the US 2024 figure is flattered by strong growth in H2 2023. Under our forecasts, underlying growth (i.e. with the carryover effect removed) would actually be slightly stronger in the euro area than the US next year (Chart 3).

On a quarterly basis, we expect both UK and euro area growth will pick up through 2024 and approach potential rates (Chart 4). The main driver of this forecast is the improvement in households’ real purchasing power. Negotiated wages in the euro area reached 4.7% in Q3, and headline inflation slipped to 2.4% in November.

The sharp fall in headline inflation rates through 2023 was mostly driven by energy base effects. These will no longer have a strong effect but we’re confident that the disinflation process will continue in Europe: underlying core dynamics look favourable, there’s still scope for food inflation to contribute negatively and inflation expectations have remained relatively well-anchored. The ECB and BoE have also tightened aggressively into restrictive territory. We expect both central banks will begin to cut rates in H1 next year and proceed with easing at a slightly faster pace than the Fed as concerns about the persistence of US inflation may endure for longer after the relative strength of domestic demand this year.

Otherwise, the picture for the US in 2024 is likely to broadly similar to that of Europe under our base scenario. Real household incomes are still set to benefit as the disinflation process continues on the other side of the Atlantic as well. We also expect that fiscal policy will remain supportive through 2024, albeit to a lesser extent than this year. All in, while we do expect a cyclical slowdown in the US after above-trend growth in 2023, we remain in the ‘soft landing’ camp.

Energy costs to remain a point of difference

The US/European divergence through 2023 has been a story of largely transitory factors weighing on European activity and unexpected resilience of US growth in the face of monetary policy tightening.

Starting with the US, it’s now clear that the economy has enjoyed a cyclical upswing driven by buoyant domestic demand through 2023. Fiscal support has provided a particular tailwind through student debt relief and Inflation Reduction Act spending. Consumer expenditure has been notably resilient, with annual growth likely to average 2%+ in 2023. On the external side, the US’s new status as a net energy exporter has also been cemented by the European rush to find alternatives to pipeline gas: US LNG exports to Europe increased 141% Y/Y in 2022.

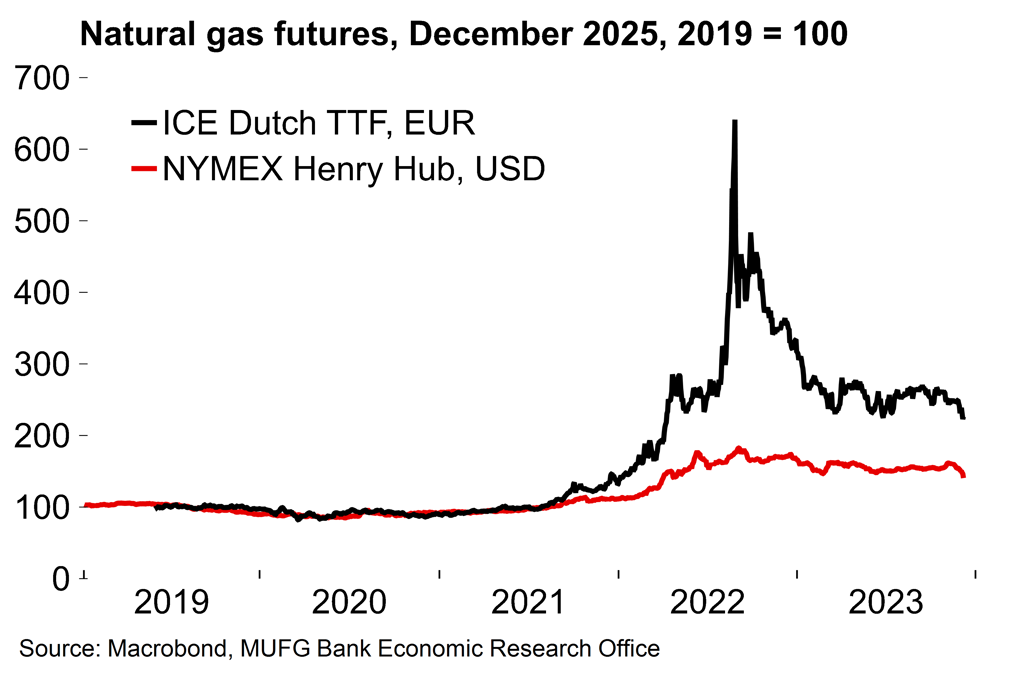

On the European side, it is last year’s energy shock following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 that is the obvious point of difference. Europe’s dependence on cheap Russian pipeline gas was suddenly laid bare as prices and volatility increased sharply. Natural gas prices increased globally as competition for LNG increased, but US price rises were nowhere near the rates seen in Europe. Governments in Europe shielded households from the full extent of price increases with generous fiscal support but the overall burden on households still increased, with higher energy costs broadly akin to a tax rise for European consumers.

Chart 5: Persistently higher gas prices leave Europe industry at a competitive disadvantage

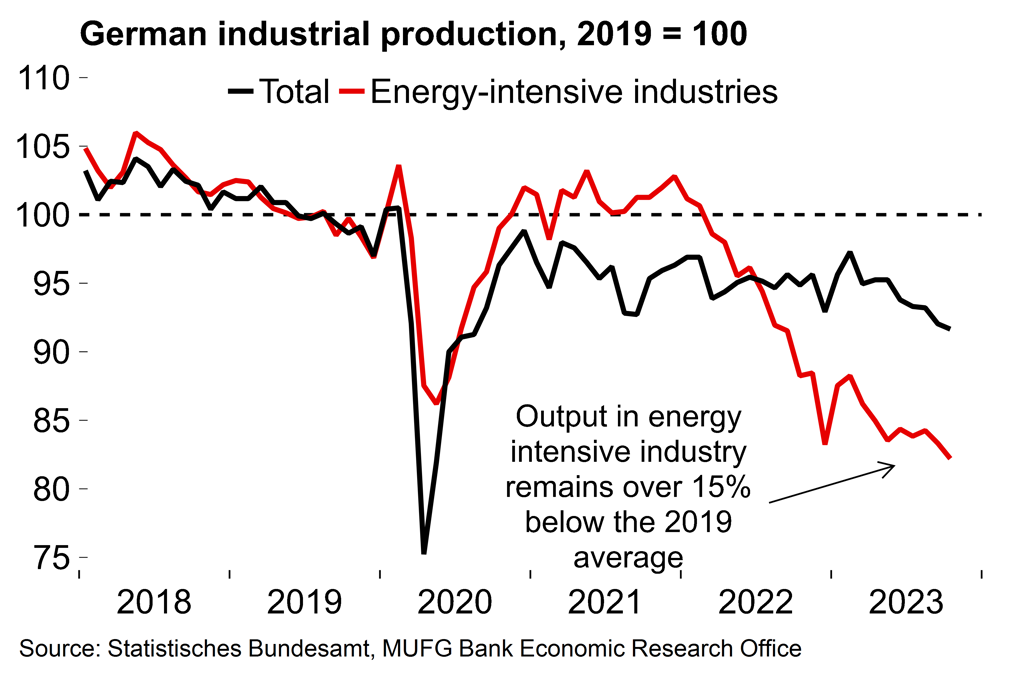

Chart 6: German manufacturing is clearly struggling with higher energy costs

While energy prices have been an obvious headwind for growth over the last year or so, we would emphasise that the European economy proved its adaptability to navigate the energy crisis on a reasonable footing, and is now well-placed going into this winter and beyond. The transition to LNG gas continues as more infrastructure comes online, and the unfortunately timed issues with French nuclear generation in 2022 have now eased. European energy supply security is no longer the key risk.

However, there is lasting divergence on prices: US Henry Hub future prices for December 2025 are around 50% above the 2019 average – for European TTF gas current pricing is around 140% higher (Chart 5). This structural shift on energy places European manufacturing at a clear comparative disadvantage vis-à-vis the US. German industrial production in energy-intensive industries remains over 15% below the 2019 average (Chart 6) and it’s hard to make a case for a rapid recovery from here. As well as the increase in energy costs, industrial output more broadly continues to suffer from weak global demand and competition in the auto industry, especially in EV manufacturing, from China.

The EU is waking up to the challenges it faces in order to remain competitive

The relative growth performance of the US and risk that more active industrial policy on the other side of the Atlantic could widen the gap further has clearly unsettled European policymakers. In her annual state of the union address in September (here), European Commission President von der Leyen said “we need to look further ahead and set out how we remain competitive”. Mario Draghi, former ECB president and prime minister of Italy, has been tasked with setting out a long-term EU strategy to increase competitiveness, with a report likely next summer.

Last week the Commission presented its priorities for the year ahead (here) which show some probable focus areas: “removing bottlenecks to private and public investment, supporting a conducive business environment, and ensuring the development of the skills required for the green and digital transitions”. These are all worthy aims, if a little vague. The hope will be that Draghi can use his clout to effect meaningful changes. The EU can react quickly to change policy in response to an acute crisis (this was demonstrated during the pandemic with, for example, the introduction of common debt). But, outside of a crisis, it can be harder to find consensus among 27 member states.

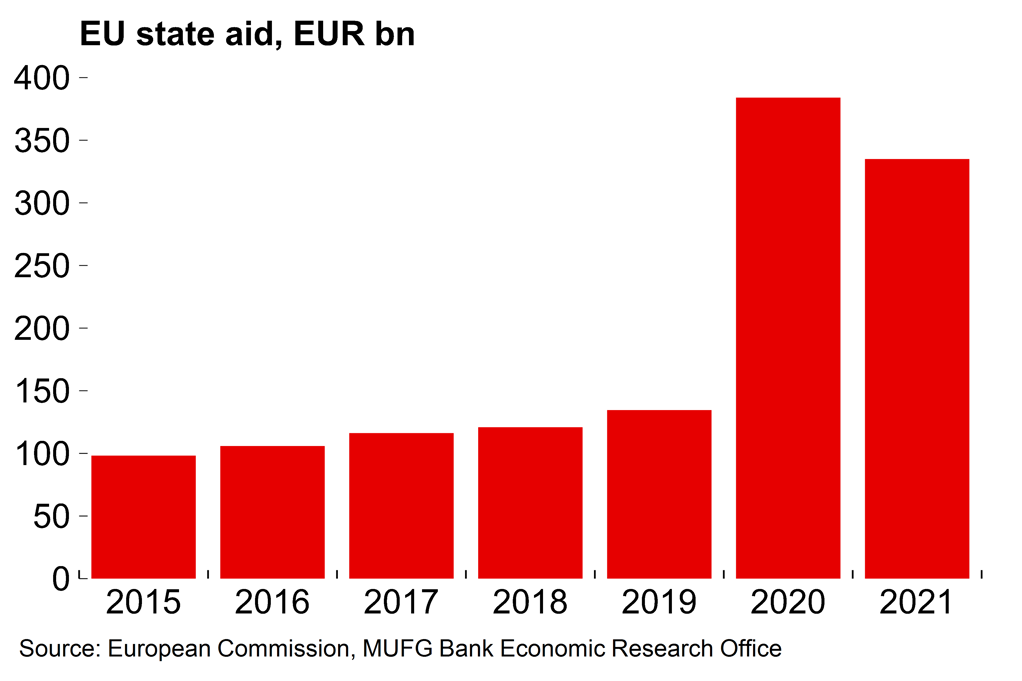

So far, the EU response to US industrial measures and the more protectionist global environment has mostly centred around leveraging existing policies which were born out of pandemic and energy crisis necessity.

Chart 7: EU discipline on state aid has gone out the window after the pandemic and energy crisis

Chart 8: US demographic outlook looks relatively good

Disbursements under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) have particularly benefitted Southern euro area countries such as Greece, Italy and Spain, which were exposed to the pandemic shock that hit the tourism industry. Perhaps more significantly – at least when it comes to international competitiveness – has been the relaxation of EU state aid rules following the pandemic and energy crisis (Chart 7). Historically, state aid has been generally prohibited to avoid distorting competition within the EU single market. It’s still too early to gauge the longer-term effects of loosening these regulations, but it seems that it has come at a good time against the backdrop of more active industrial policy in the US. That said, it could pose risks to EU cohesion if ‘national champion’ firms in richer member states are the main benefactors (which seems likely).

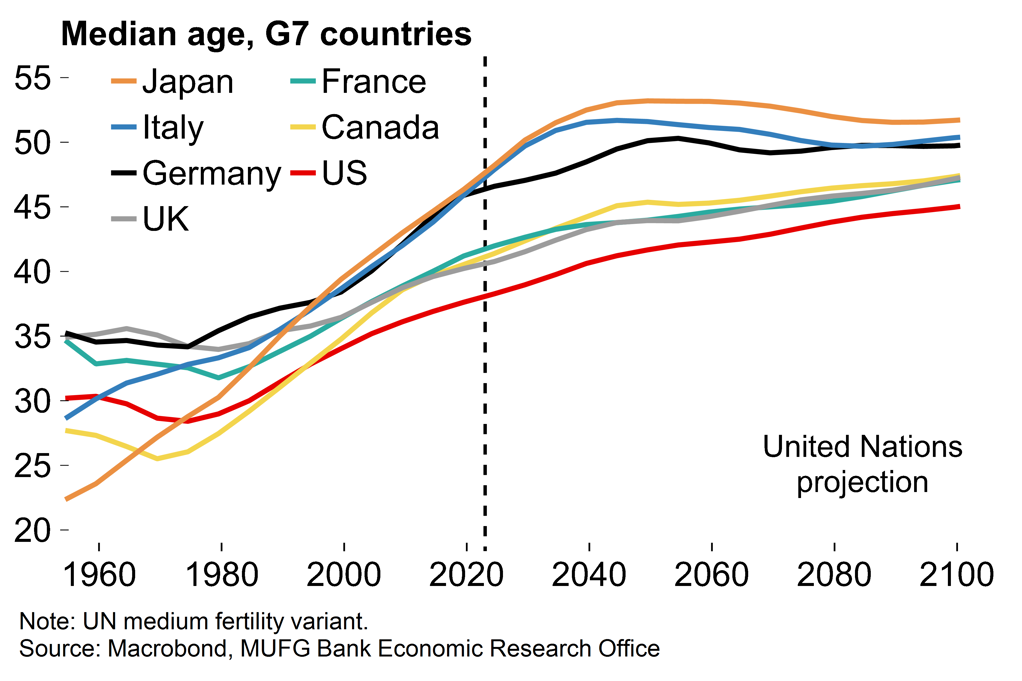

Our broad view is that without radical change – such as more fiscal integration (something Draghi has called for previously) – Europe will likely struggle to close the gap to the US over the longer term. We are not holding our breath when it comes to meaningful reform measures on the EU side. Meanwhile, the US demographic outlook is more favourable than in Europe (Chart 8) so the gulf in overall output looks set to widen further over a longer horizon, even if efficiency improvements can be found.

Different inflation drivers – but the same monetary policy treatment

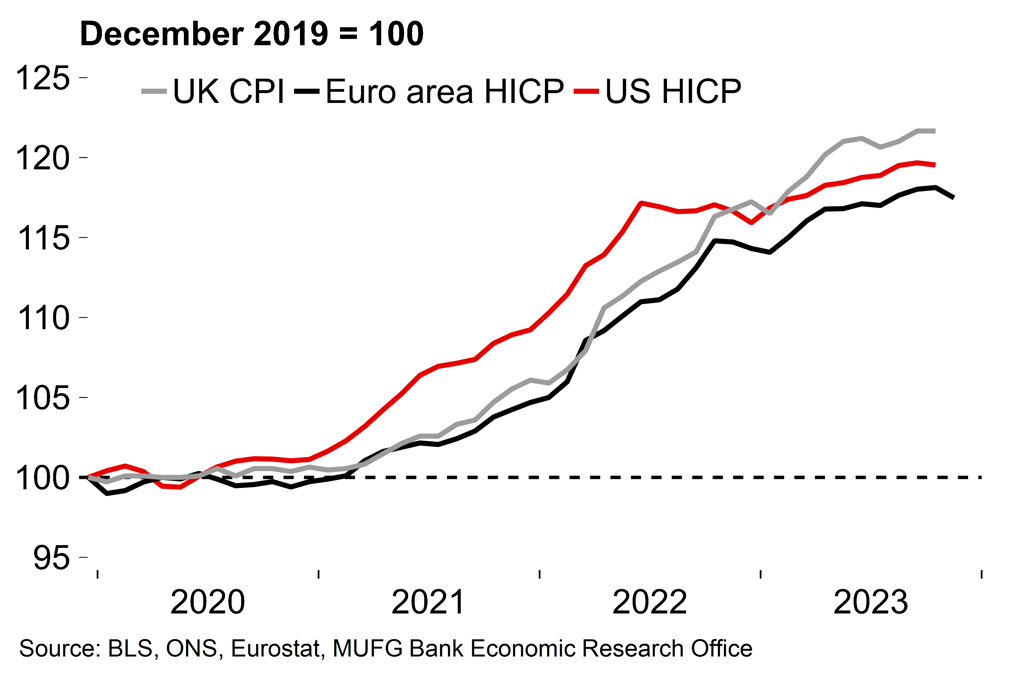

GDP growth rates may have diverged this year but US prices have followed a remarkably similar path to that of the euro area and UK when looked at in levels. We use the US HICP measure as the best index for direct comparison (Chart 9). Demand-driven pressures in the US have essentially led to a similar inflation outcome as the supply-side energy shock in Europe.

Chart 9: The increase in price levels has been remarkably similar on each side of the Atlantic

Chart 10: The central bank response has been almost identical – did the ECB/BoE do too much?

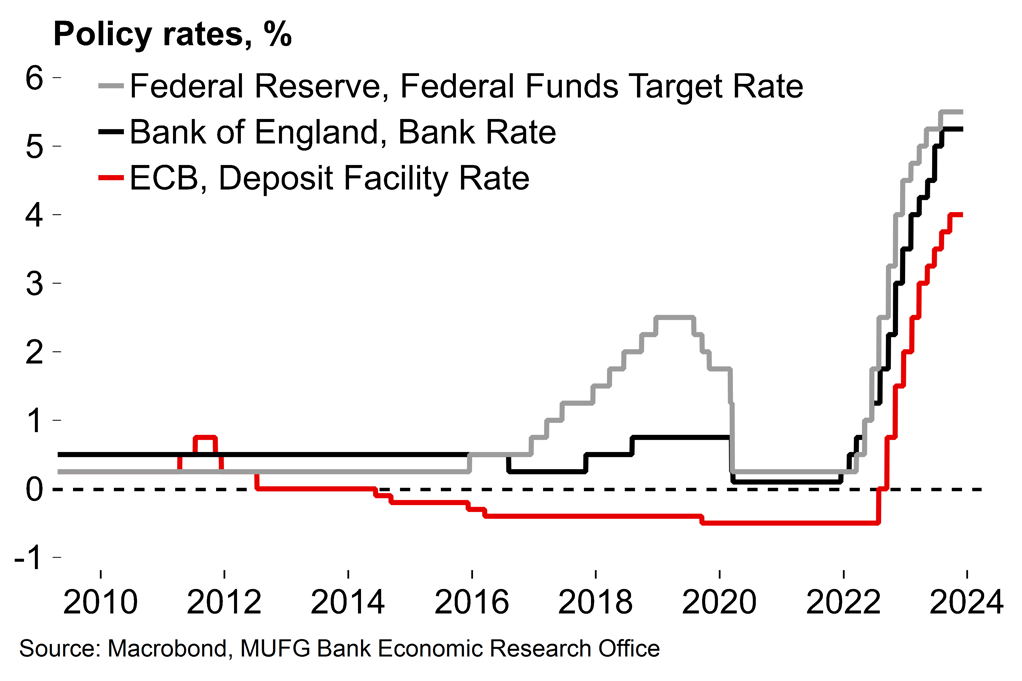

Despite the different drivers of inflation, central banks on either side of the Atlantic have applied very similar treatment (Chart 10). The BoE was the first major central bank to raise rates after the pandemic, back in December 2021. Since then it has more or less mirrored the Fed’s rate hike cycle on the way. The ECB also followed a similar tightening path, eventually.

Our view is that the neutral rate of interest (at which monetary policy is neither expansionary nor contractionary) has increased by more in the US. Or, to put it another way, the US economy has been able to absorb interest rate rises more easily than the European economy.

This means that it is more likely that the ECB and the BoE have committed a policy error than the Fed to our minds, not least after a longer period of rates at, or close to, the lower bound. Our base case is that the US outperformance narrative will fade in 2024 as the US economy undergoes a cyclical slowdown and euro area/UK activity holds firm as real household incomes recover. But the risks to our European growth forecasts remain tilted to the downside given lingering uncertainty about the lags and effect of monetary policy tightening on the economy.