- The UK data flow has been broadly favourable for the BoE since the first cut in August but policymakers are divided around underlying inflation pressures and clearly do not share the Fed’s urgency to dial back policy restrictiveness. The BoE's guidance is still for a gradual pace of easing ahead.

- Given that, our base case remains that the next move will be in November and that the BoE will proceed with a quarterly pace of cuts into next year - but risks are tilted towards faster action. The government’s first Budget at the end of October looks key and could provide cover for a pivot if there’s a sense by then that the BoE is at risk of falling behind the curve.

No recalibration from the BoE

The BoE left rates unchanged yesterday, as expected, in what is likely to have been a fairly straightforward decision. Since the first cut in August came with a finely balanced 5-4 vote it has been clear that it would be hard to find a consensus for back-to-back moves. The vote split this time (8-1) shows that that the MPC is more united when it comes to maintaining the holding pattern. We had expected a 7-2 split.

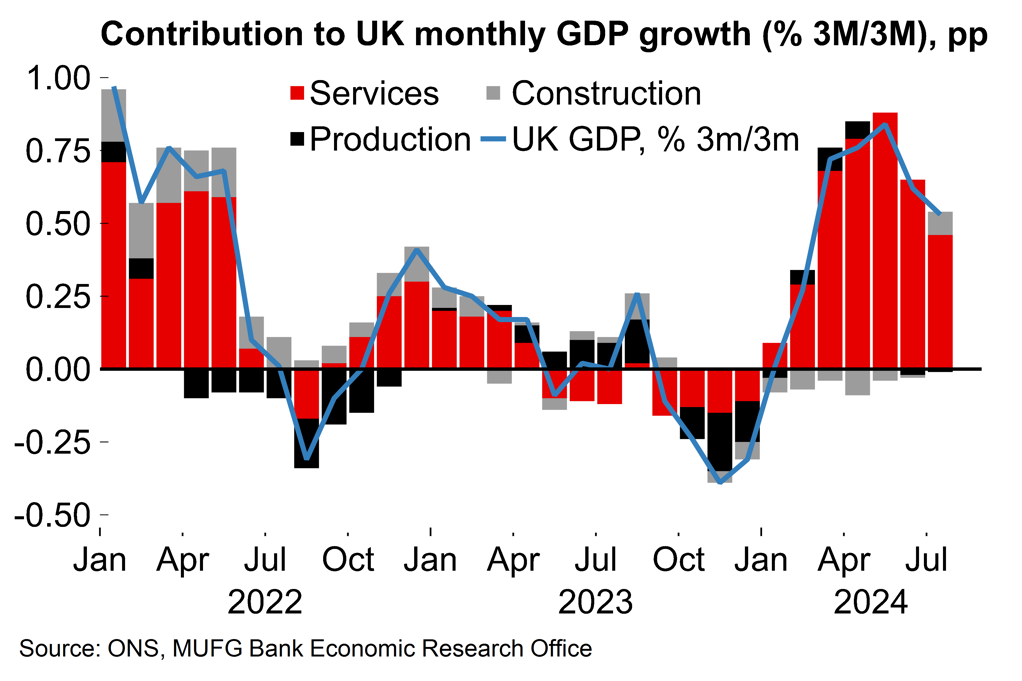

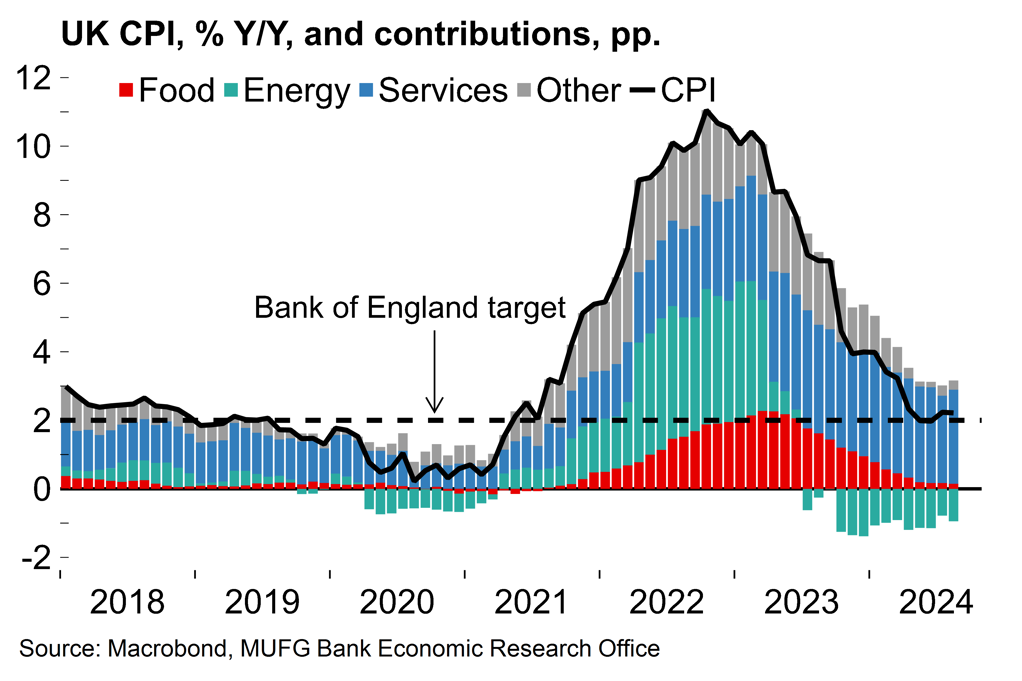

The data flow since the first cut in August has been mostly positive from a monetary policy perspective. The recent weakness in monthly output figures will have reassured policymakers after above-trend growth at the start of the year. Indeed, the BoE now looks for GDP growth of 0.3% in Q3, down from 0.4% in the August report. On inflation, this week’s headline, core and services figures were all in line with expectations. Services inflation moved up to 5.6% in August, from 5.2%, but this was largely driven by base effects and volatile components such as air fares. Looking ahead, the headline rate is likely to dip lower in September and then increase in Q4. However, the recent move downwards in oil prices means that cheaper fuel will help to offset the October increase in household energy bills.

Chart 1: UK growth has cooled in recent months

Chart 2: Headline inflation is now hovering around target

So, broadly good news on the data front. But as we noted in our preview (see here), the BoE is not devoutly data dependent in the way that the ECB is currently. That is, officials are happy to set out at least some guidance about the pace of future easing and will not necessarily change that in reaction to new data.

This meeting’s statement noted that “a gradual approach to removing policy restraint remains appropriate” and speaking after the decision Bailey said that the BoE has made “a lot of progress” and is “now on a gradual path down”. It was also stated again that “monetary policy will need to continue to remain restrictive for sufficiently long until the risks to inflation returning sustainably to the 2% target in the medium term have dissipated further.” All told, this is not language to tee up back-to-back (or indeed 50bp) rate cuts.

Risks are tilted towards a faster pace of easing ahead

What next? Our base cut remains for the next BoE cut in November, then a pause, then another move in February. That would be consistent with the guidance. But risks are tilted towards a faster pace of easing. By the next meeting (7 November) policymakers will have more information about the extent of fiscal consolidation coming down the track. The UK PM has already said that the new government’s first Budget (30 October) will have some “painful” consolidation measures which means that the UK will soon have fiscal and monetary policy pulling in opposite directions. This could provide scope for a pivot to faster easing from the BoE, whether in direct response to new fiscal measures themselves, or by offering some cover if there’s a sense by then that the signalled steady pace of easing might leave the BoE behind the curve.

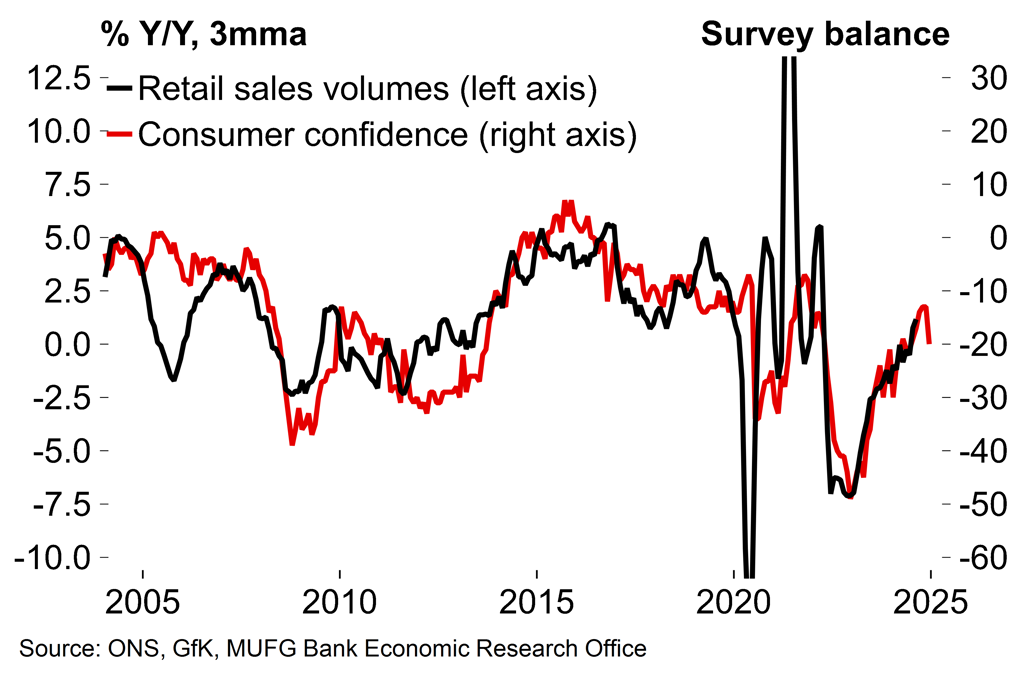

On the economic backdrop, a steady expansion next year, driven by household spending, remains our base case. The overall picture for consumers still looks broadly favourable as real incomes recover. Retail sales volumes in August grew by 1% M/M and reached a two-year high. But there may be some jitters around the outlook over coming months. Data today showed that consumer confidence plunged in September. We suspect this is a temporary blip related to uncertainty around upcoming Budget measures – it’s generally not great for confidence when officials warn of “painful” measures ahead. Indeed, there’s a sense now that the government may have overdone the gloomy messaging in an attempt to pin problems on the previous administration and that this is weighing on broader sentiment. That could be reflected in the flash PMIs next week too. But we suspect there may be a shift towards more positivity about the outlook from officials over coming months, especially as the government implements more of its own policies.

Chart 3: Consumer conditions have improved

Chart 4: Retail sales volumes continue to recover

Looking ahead, focus will increasingly turn to the question of how far rather than how fast when it comes to rate cuts. Given how divided the MPC was around the initial cut in August it’s clear that there’s likely to be a wide range of views on the question of how many cuts are possible before policy ceases to be restrictive. We have pencilled in a terminal rate of around 3%, all else equal, but would expect dissent from more hawkish members of the MPC before rates reach that mark. Future decisions are unlikely to be as straightforward as yesterday’s hold – there will be plenty of communication challenges ahead for the BoE.

UK policymakers do not share the Fed’s urgency to dial back restrictiveness, for now

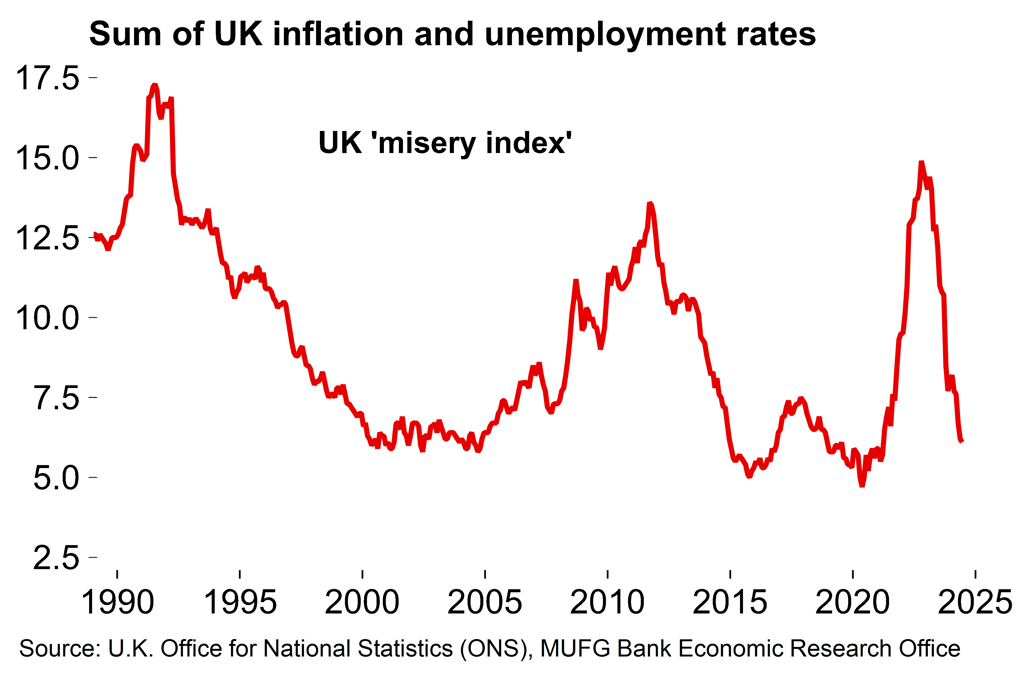

For now it’s clear that the BoE does not share the Fed’s urgency to dial back restrictiveness. Recent UK data may have been broadly positive but the hawks on this side of the Atlantic still have plenty of ammunition. Inflation is clearly elevated compared to the start of previous easing cycles with the services component notably high. Nominal pay growth also remains uncomfortably elevated from a monetary policy perspective.

A more proactive Federal Reserve will also raise expectations around a US soft landing, which in turn reduces an obvious risk to the UK growth outlook (the UK services sector has been in fairly good shape since the turn of the year and would be exposed to a US downturn). That will bolster the case for a steady approach from UK policymakers.

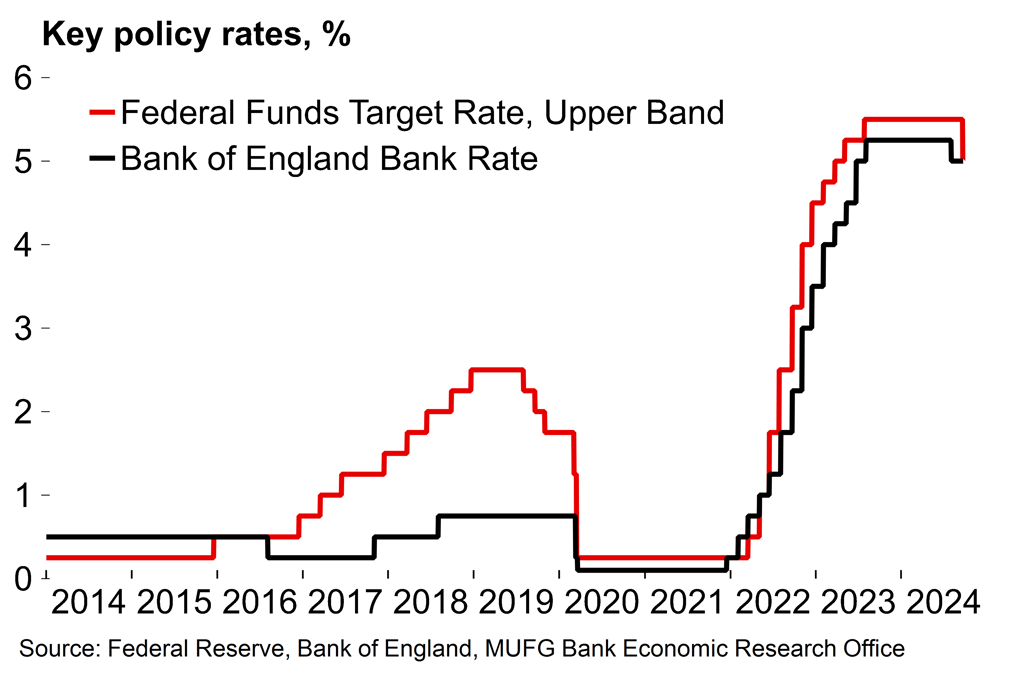

Chart 5: The BoE moved first but was soon playing catch-up with the Fed during the tightening phase

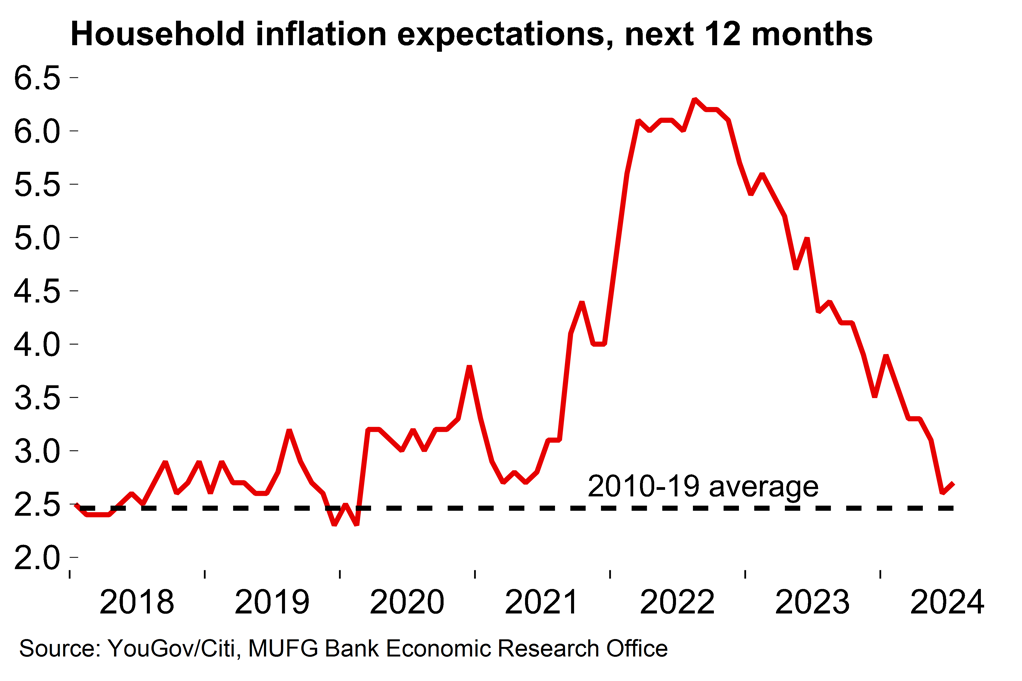

Chart 6: Household inflation expectations have now normalised

But it’s also worth looking at the tightening phase of the cycle. The BoE was the first major central bank to raise rates, but it was soon playing catch-up with the Fed (and even ended up at a very similar peak rate) despite different drivers of inflation. Does that show a revealed preference on the part of the BoE to limit divergence?

We suspect that officials in the UK will be glad to have moved before the Fed again, especially in light of its emphatic start to the easing cycle, in what could be seen as sign of the BoE’s independence of thought. But, while there is less alignment in terms of guidance right now, increased expectations around more forceful cuts in the US and hence further GBP outperformance could be another reason for the BoE to pivot towards faster pace of easing further down the line.

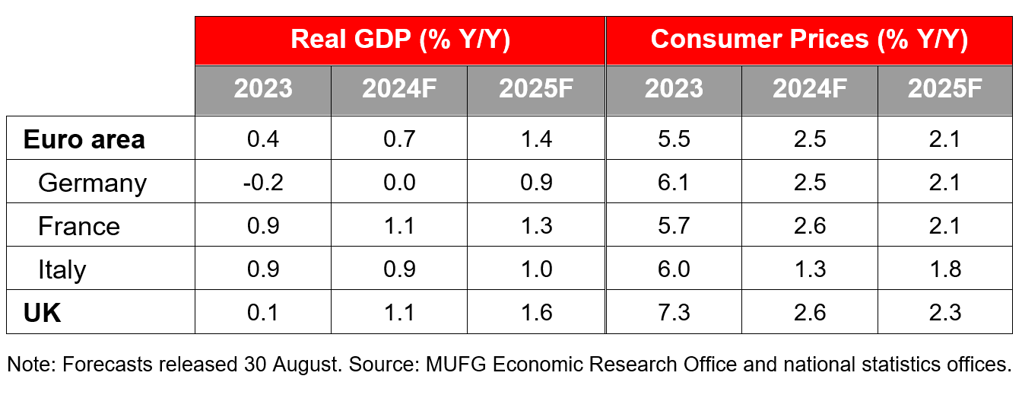

GDP & CPI forecasts