- From a European perspective, the new US 20% tariff on EU goods is not a huge shock. The next few days may reveal if there is scope for negotiation and whether the 10% baseline rate is a hard floor.

- Attention will also turn to the EU response. There is a clear preference for dialogue but policymakers seem ready to implement targeted and proportional countermeasures. The scope of these could move beyond purely goods trade and into the services market. Watch also for anti-dumping measures after several EM economies were hit hard by higher US tariffs.

- Any estimate of the growth impact at this stage needs to be taken with a pinch of salt given the wide range of moving parts. As an indicative number, the near-term, static effect on euro area GDP from the tariffs alone might approach 0.5%. This will be magnified by the drag from the associated confidence shock, weaker external demand and supply-chain disruption. Fiscal reform in Germany will provide a significant cushioning effect but two more years of sub-1% euro area growth now seems very plausible.

- The impact on the UK will be smaller – it faces the baseline 10% tariff only and has lower goods exports to the US as a share of GDP. The UK government also seems less inclined to retaliate and so there may not be an inflationary effect from countermeasures. Still, the overall growth impact on the UK is unlikely to be negligible for an economy which carried little momentum into the year.

The ‘tariff man’ delivers

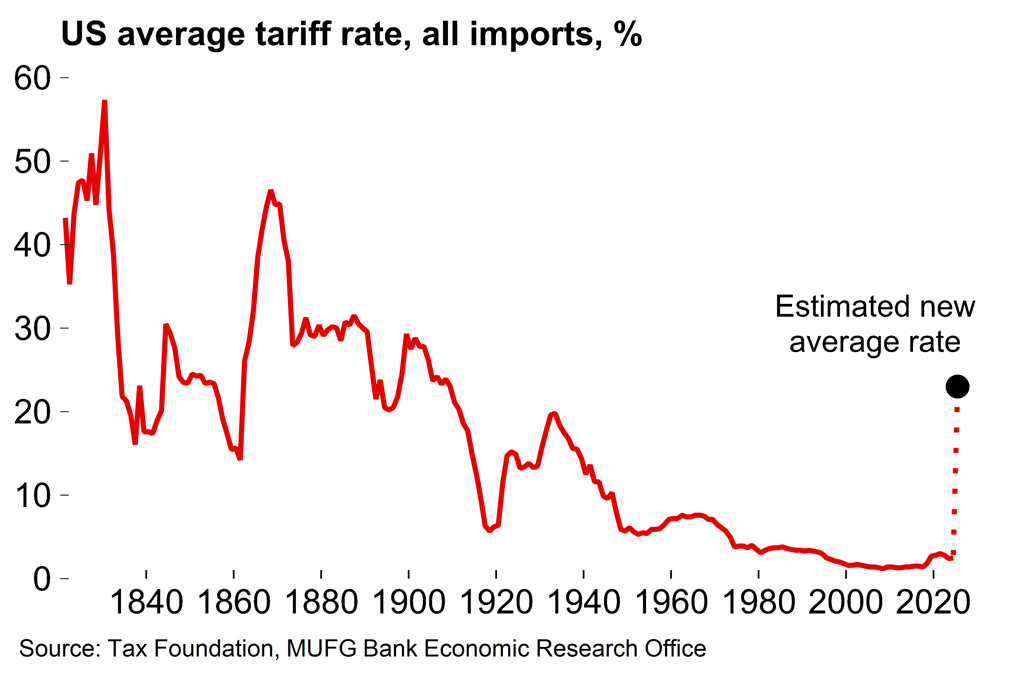

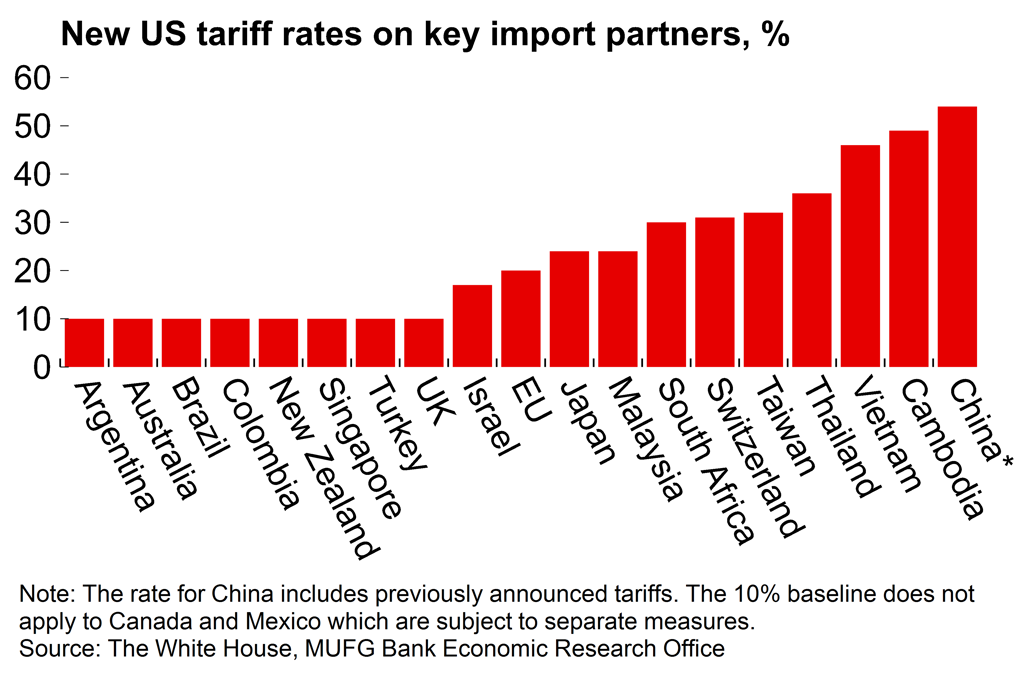

The US president announced a baseline 10% tariff on all imports to the US which will take effect on 5 April. Customised ‘reciprocal’ tariffs are also to be applied to certain trading partners (these are seemingly calculated on the basis of each country’s goods trade surplus with the US rather than specific barriers to trade). The customised tariffs will take effect on 9 April, while the previously-announced 25% tariff on vehicle imports is also now effective. The whole package is likely to take the average US tariff rate to around 20-25% – a level not seen since the 1930s.

The rate applied to the EU will be 20% - marginally less severe than the 25% tariff previously threatened by President Trump. The UK, which doesn’t have any meaningful goods trade imbalance with the US, faces the 10% baseline rate.

The US administration seems to have a range of goals associated with these tariffs. These include: 1) to boost domestic US production, 2) as a source of revenue to offset tax cuts and 3) to use as geopolitical leverage to extract concessions from other countries.

The first two ambitions suggest that higher baseline tariffs are here to stay, at least in some form, but the fact that the higher customised rates will not be applied until slightly later on may be seen as an invitation to negotiate. Developments over the next few days may reveal how much scope there is for countries to negotiate lower tariffs, if any, and whether or not the 10% rate is seen as a hard floor to US tariffs.

The US lurches towards protectionism

Higher rates for several key US trading partners

How aggressive will the EU response be?

In her initial statement, European Commission President von der Leyen emphasised that the EU is ready to discuss barriers to trans-Atlantic trade – but is also preparing a list of retaliatory countermeasures “if negotiations fail”. As of this month the EU has already restored previously applied countermeasures from 2018 and 2020 and will announce further measures by mid-April in response to previously announced US tariffs.

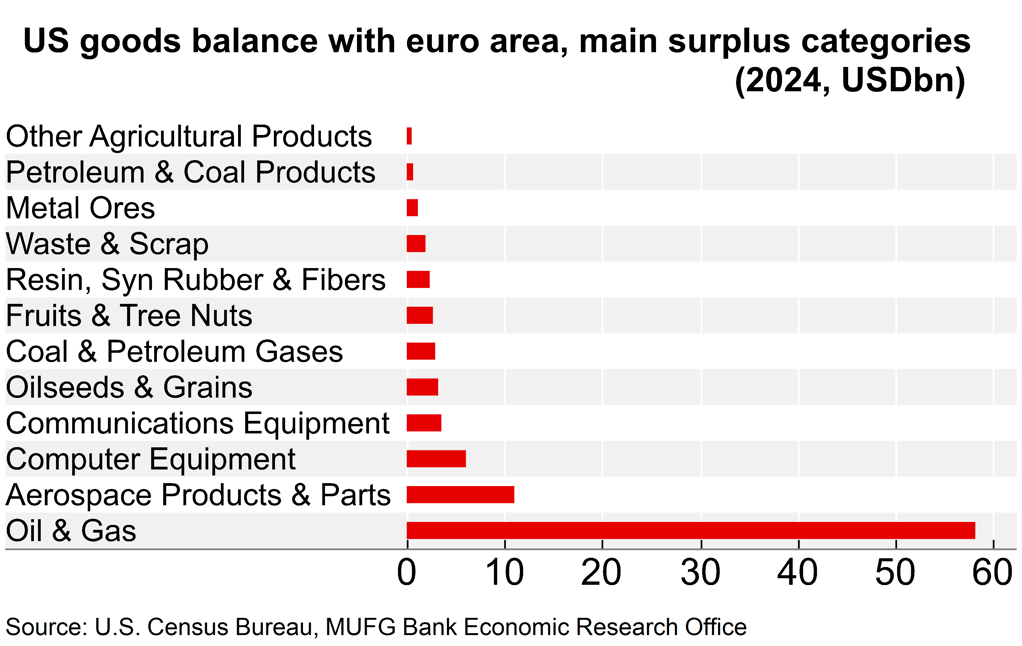

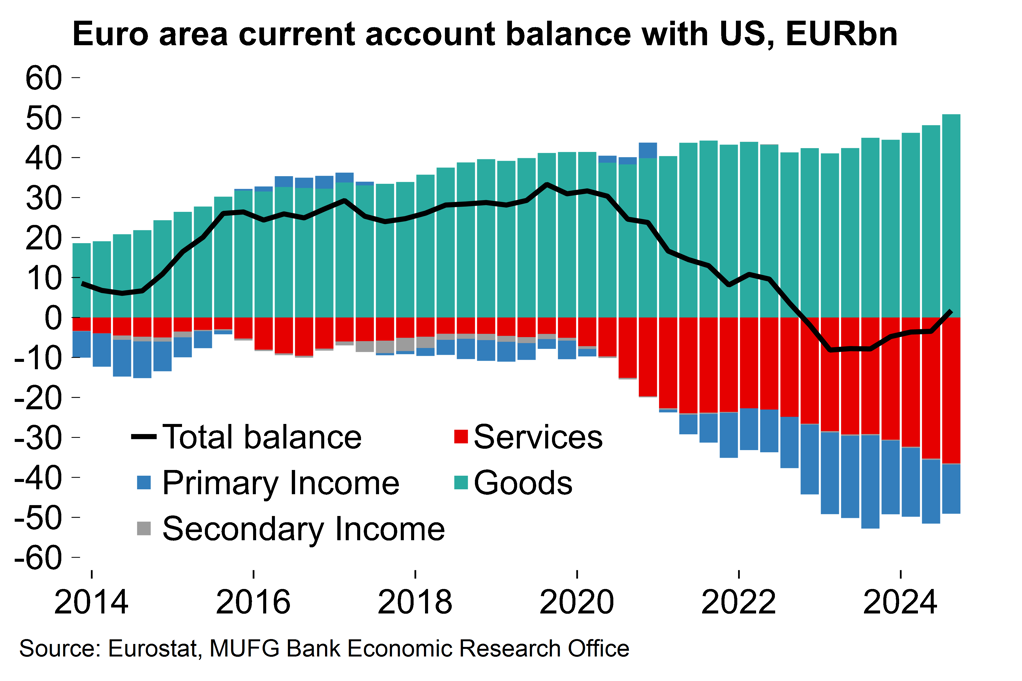

Initial countermeasures will cover the obvious goods imports (i.e. politically-sensitive and more readily substitutable). Finding further targets to match the scope of new US tariffs may be tricky. The main source of goods ‘imbalance’ is in energy – oil and gas accounts for over 20% of total US exports to the euro area – and that is unlikely to be targeted.

So the EU may be moved to take a wider view of its trading relationship with the US, which is roughly in balance when including services. Since Trump’s first time the EU has also announced an ‘Anti-Coercion Instrument’. This provides a legal framework for retaliatory measures to expand beyond goods tariffs and into areas such as restrictions on trade in services, intellectual property rights and public procurement. While on paper this looks to be a typically-slow EU process, policymakers showed during the pandemic and energy shock that they can act more quickly in a crisis.

It’s also worth noting that the EU seems mindful of the risks of product diversion to the European market. The new US tariff on Chinese goods, including previous measures, will exceed 50%, and various other Asian EM economies face high US tariff rates. Von der Leyen stated today that the EU “cannot absorb global overcapacity” and so it seems fairly likely that the EU could introduce measures such as import quotas to protect against dumping.

Where does the US have a surplus in goods?

Overall US-euro area trade is broadly balanced

The euro area recovery is set to stall

Fully quantifying the impact on growth from this US lurch to protectionism is essentially impossible at this stage, but we can set out some ballpark numbers which are indicative of our initial views.

In terms of the static effect of new tariffs, euro area goods exports to the US are equivalent to around 3% of GDP. An elasticity of -0.75 (see here) would imply a direct GDP impact of 0.45%. On top of that, we expect indirect effects from 1) a confidence effect for both businesses and consumers, 2) weaker growth elsewhere (the immediate outlook has weakened for the US and China), 3) a boost to domestic inflation from retaliatory measures and 4) international supply chain disruption as trade is re-routed.

On the confidence effect, the shock is likely to be mitigated by the blockbuster German fiscal reforms. We won’t know the details for a while, but new spending could now be more front-loaded than initially planned to help mitigate the drag from tariffs. Policymakers may also introduce further measures (e.g. targeted support for most affected industries) to cushion the blow. There could also be more urgency to speed up structural reforms to reduce red tape and improve European competitiveness.

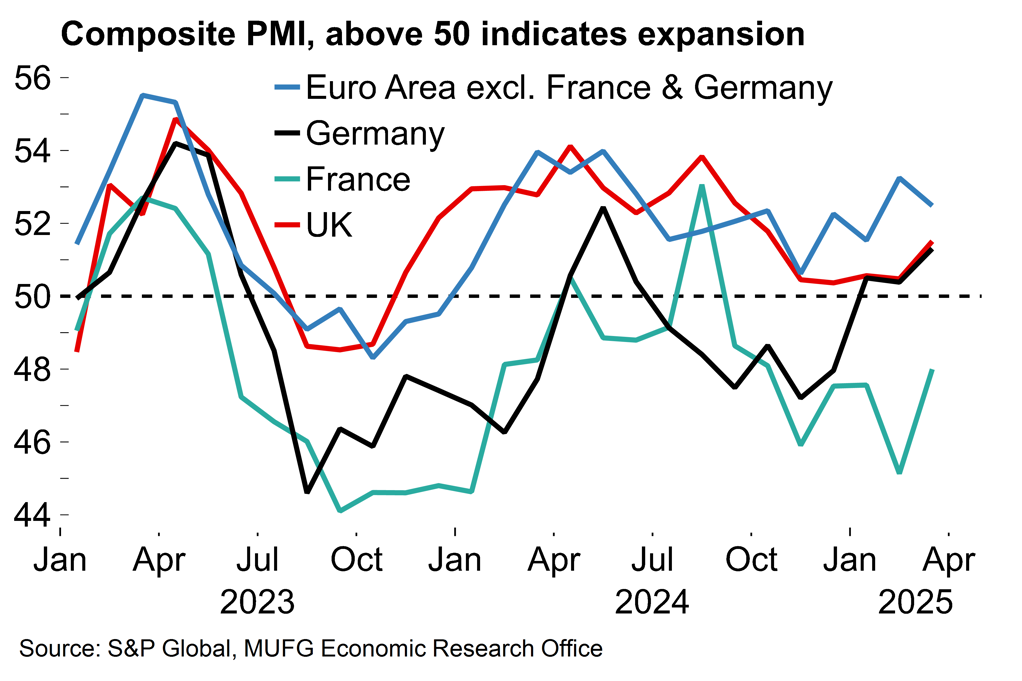

For now, we stress that the recovery is fragile. Current euro area survey data, even after recent improvement, is still only consistent with muted overall growth at the start of the year. At least part of the boost to manufacturing confidence numbers is likely to have been related to stronger demand from US importers looking to front-load procurement from abroad ahead of any possible tariffs. The reversal of this trend will be an extra headwind for short-term growth.

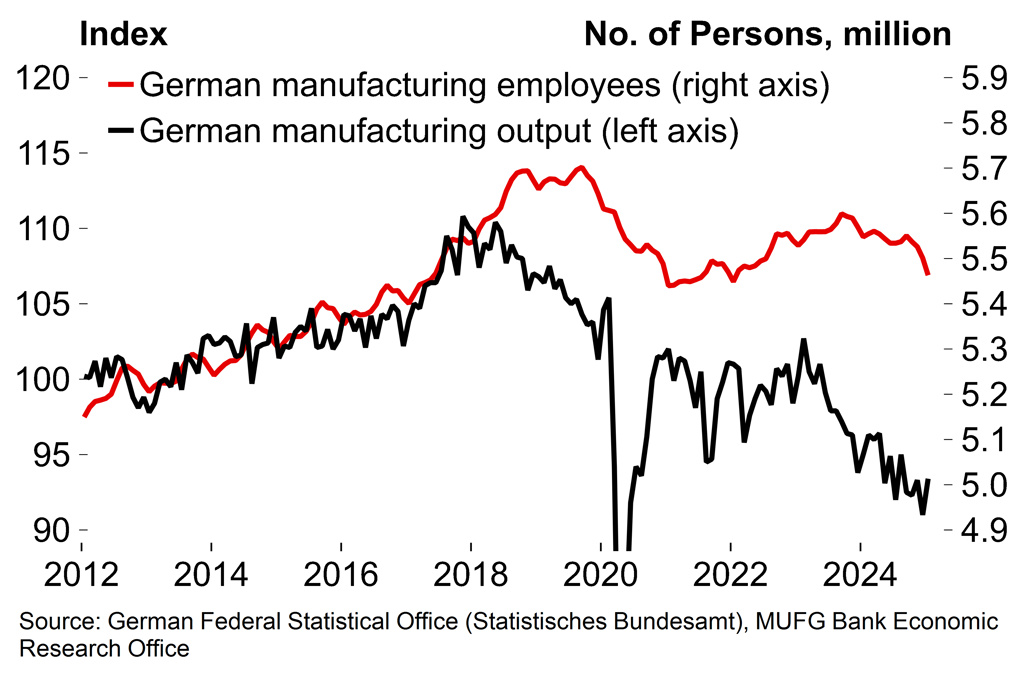

There are also risks of sharper second-round effects on manufacturing employment. After signs that firms may have been ‘hoarding’ workers (see here), Trump tariffs could be the trigger for firms to pull the trigger on redundancies, which could significantly deepen the downturn.

All told, we are initially pencilling in an impact in the region of 0.9pp on euro area GDP growth, spread over 2025 and 2026. That’s somewhat in line with the ECB estimate that 25% US tariffs followed by EU countermeasures would lower growth by around 0.5pp in the first year. Our pre-tariff euro area forecasts put growth at 0.9% in 2025 and 1.4% in 2026. We will refine these estimates and provide a full forecast update over coming weeks.

On inflation, there would be some immediate upward pressure from any retaliatory measures but our view remains that tariffs are ultimately likely to be disinflationary given the overall impact on demand. On top of that, that scope of the tariff shock has increased risks of further downward pressure on price growth from trade diversion and weaker commodity prices.

Euro area inflation data this week was also encouraging, even accounting for volatility from the timing of Easter, with core inflation falling from 2.6 to 2.4%. The ECB will be keen to retain plenty of flexibility given uncertainty around the impact on the economy and the EU response. But the conditions may fall in place for interest rates to move slightly below the mid-point 2% estimate of ‘neutral’ later this year, which would provide some further support to economic activity.

European sentiment has generally improved since the turn of the year

German firms have been somewhat reluctant to make lay-offs – will that change?

The UK economy is less exposed but will still suffer

The impact on the UK economy will be smaller, but not negligible. The US is the UK’s largest (national) export partner, accounting for 27% of UK services exports and 15% of UK goods exports (see a summary of the flows in ONS data here).

Relative to the euro area, the UK has slightly lower goods export exposure to the US (2% of GDP) and is only faced with tariffs at the 10% baseline. The same approach used above implies a direct impact of 0.15% of GDP. On top of that, the UK will be exposed to weaker growth in the euro area and elsewhere, as well as the confidence effects and supply-chain disruption previously mentioned. On the other hand, the UK government seems less likely to retaliate than the EU and so there may not be an inflationary effect from countermeasures.

For now, we have pencilled in an overall UK growth impact of around 0.4pp. Unlike in Germany, the UK government has little room for manoeuvre in terms of a policy response to boost demand. The new spending announced last autumn was already front-loaded (see here) so there will be some cushioning effect. But the limited remaining headroom against the fiscal rules was subsequently eroded by higher interest costs and slower growth which forced the chancellor to trim spending plans. A slowdown in activity following the Trump tariff shock will further reduce the government’s fiscal headroom and raises the chances of tax rises later this year (see here).