- The German fiscal policy announcement is a huge positive demand shock which is set to be reflected in business sentiment immediately. That is likely to boost growth this year, but the direct effects of new spending are unlikely to be felt until 2026. The details will be crucial but at this point we estimate a ~0.8pp boost to German growth next year which would take the annual average rate to around 2%. This could jolt the economy into life after an extended period of stagnation with clear scope for enduring productivity gains and stronger private investment. Immediate risks around the growth outlook, which were dominated by the possibility of tariffs, are now suddenly a lot more balanced – and tilted to the upside over the medium-term.

- The ECB cut rates again yesterday but noted that policy is becoming ‘meaningfully’ less restrictive now. This helps to tee up the possibility of a pause at some point in coming months to the current cycle of consecutive rate cuts. Policymakers clearly want to retain flexibility, though. By the next meeting in April there will be more clarity around domestic fiscal policy and there may be some around new US tariffs.

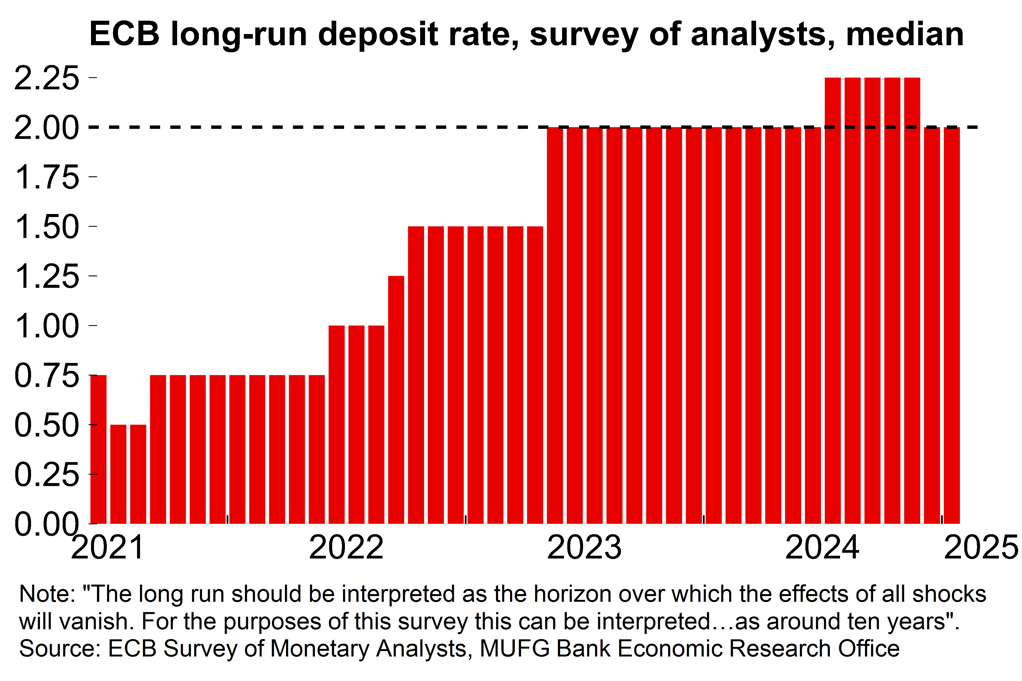

- The ECB is not discussing the fiscal policy announcement in Germany before it is formally confirmed and the details are clearer, but to our minds the chances of rates falling into accommodative territory (i.e. <2%) have now been reduced given the increase in demand coming down the track. Indeed, the huge rise in German investment and possible productivity boost over the medium-term will bolster any arguments that risks to neutral rate estimates may lie on the upside.

I am back in the office after a month of paternity leave. In that time, it appears that a trade war has begun, the transatlantic alliance has collapsed and there has been a sea change in German fiscal policy. Other than that, I gather it’s been quiet...

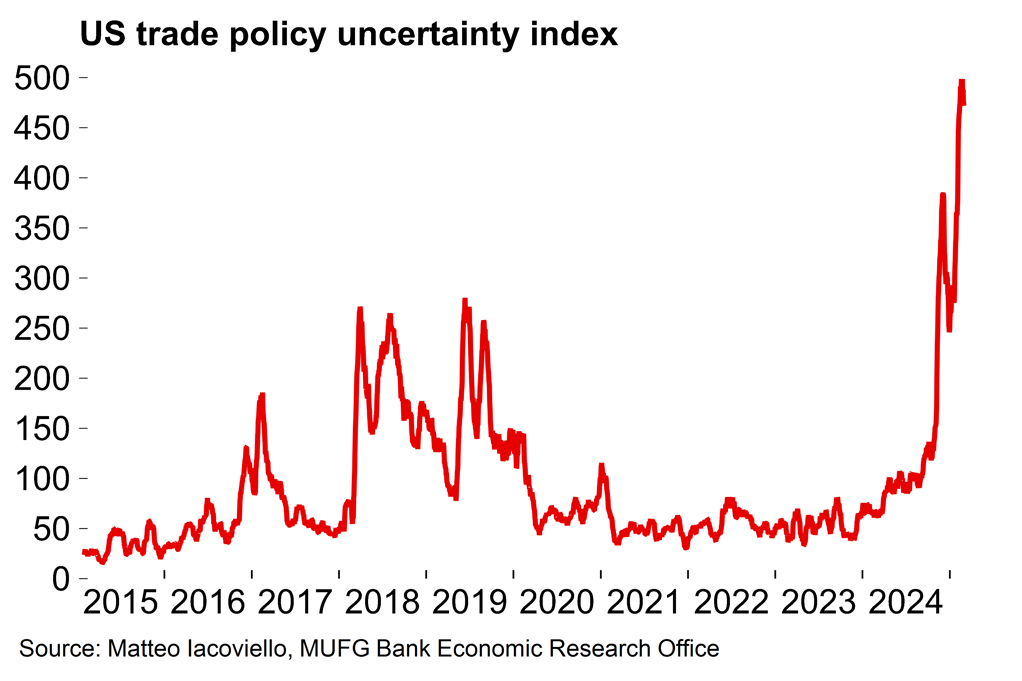

On the first point, US trade policy towards Europe has evolved broadly as we expected: the opening salvo, with targeted measures only, duly proved more moderate than Trump’s pre-election rhetoric suggested. Of course, that could change rapidly and the threat of rapidly expanded measures will continue to loom over European producers.

The geopolitical realignment is not entirely unexpected either. We wrote back in October that “Trump 2.0 might just be the driver for the EU to take more decisive action on issues such as defence, energy independence, digitalisation, deregulation and more active industrial policy”. However, both the untangling of the transatlantic alliance and the European response have certainly been faster and more forceful than anticipated.

But it’s the huge shift in German fiscal policy which is by far the most significant development of recent times from a European perspective. The numbers are simply staggering. New chancellor Merz hinted prior to last month’s election that there could be some adjustment to Germany’s debt brake constraints – but there was nothing to suggest any change on this scale during the pre-election discourse (a summary of the CDU/CSU programme can be seen here). It is a huge, positive demand shock.

Trade policy uncertainty has moved well beyond that of Trump’s first term

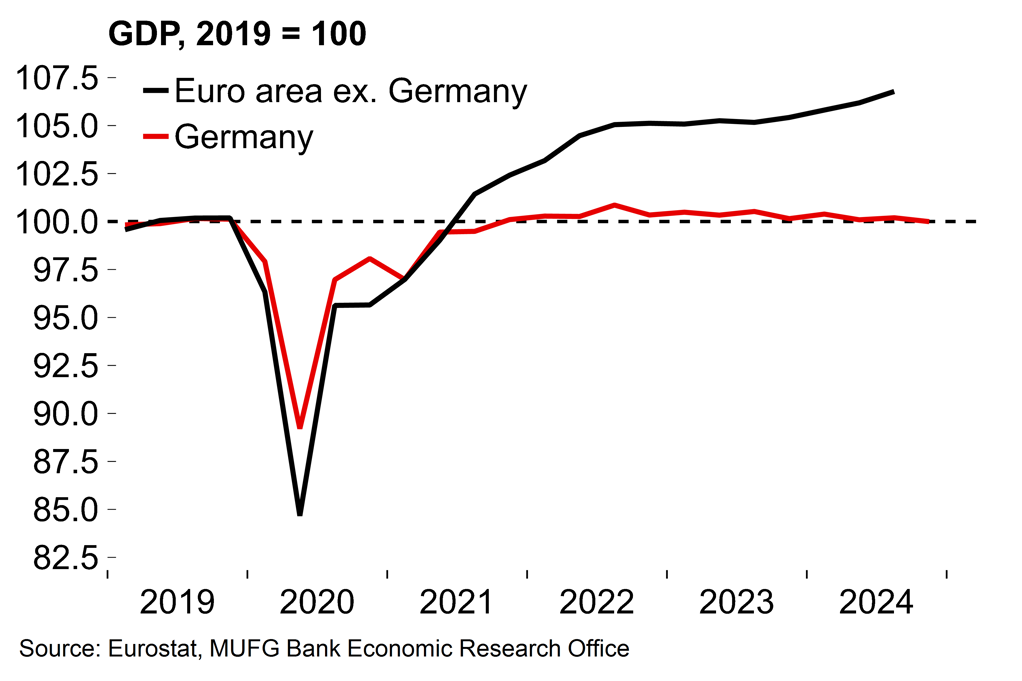

Germany has dragged on euro area growth

The brakes are off in Germany

The CDU/CSU and the SPD (who are most likely to form the next government) have proposed hugely significant changes to German fiscal policy. The constitutional debt brake is to be adjusted so that defence spending above 1% of GDP will be exempted, while regional governments will be allowed permitted to borrow up to 0.35% of GDP (which is the current limit to central government borrowing).

And then there is the proposal for a 500bn EUR special fund for infrastructure. That is to be disbursed over 10 years and 1/10 of it would represent around 1.2% of 2024 GDP. The fiscal multipliers associated with this sort of government spending are solid: it is all spent domestically and cannot be saved.

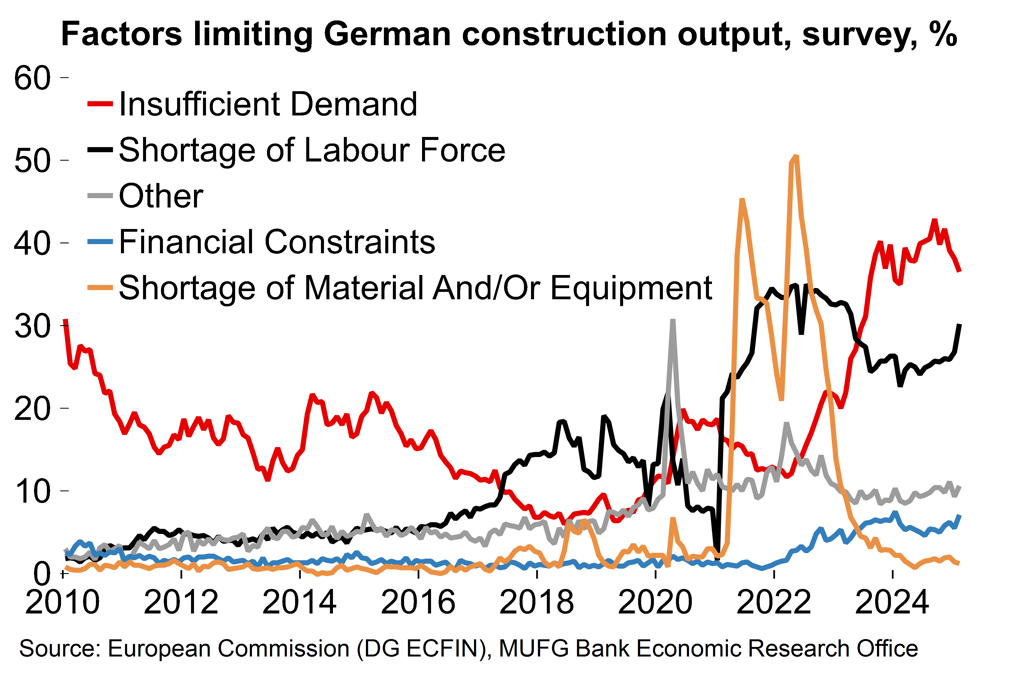

However, timing will matter when it comes to the impact on GDP growth. Infrastructure projects generally have long lead-in times and survey data suggests that limited worker availability is still a drag on the construction industry. The electoral cycle could also be pertinent as the government may be tempted to hold back some firepower for the run-up to the next federal vote in 2029. Given this, we judge that it’s unlikely that the fund envelope with be disbursed linearly over its duration. We assume that there will be little direct effect on 2025 growth (although the confidence effects could be sizeable) and then a more meaningful boost to activity from 2026.

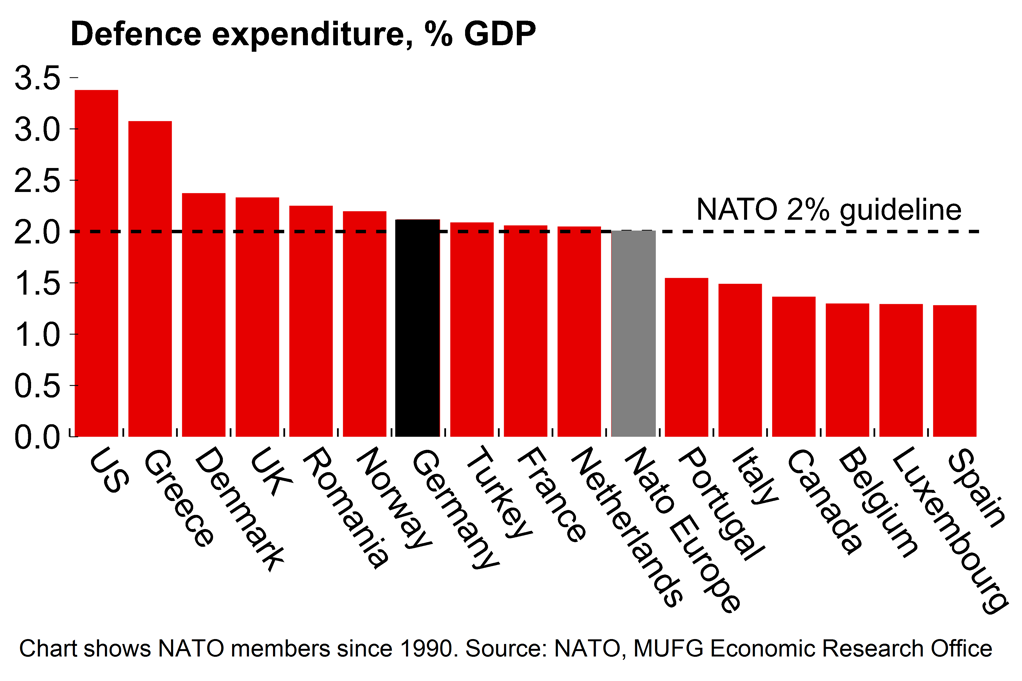

There is more uncertainty around the effect of the carve out of defence from the debt brake borrowing limit. On paper, it gives open-ended scope for defence spending to rise from the current 2.1% of GDP. We assume the aim will be to move to above 3%, but we don’t know how fast the government will aim to reach that mark, or what the split will be between personnel recruitment and equipment/infrastructure. Broadly speaking, the fiscal multipliers from new defence spending, at least over the short-term, are likely to be worse than those for infrastructure.

On defence procurement, it is likely that only a small share of new spending will be captured domestically over the short term. While Germany is a manufacturing-orientated economy, SIPRI data shows that German firms account for just 1.7% of the arms revenues of the world’s top 100 producers. Indeed, the Draghi report noted that 78% of EU defence procurement was from non-EU suppliers and 63% of that was accounted for by the US. There may be some political pressure to shun US suppliers and promote German or wider European producers, but it will be essentially impossible to do that over the short term given military industrial capacity in Europe currently.

German defence spending is now set to rise sharply above the current NATO guideline

How fast can infrastructure projects be implemented given labour shortages?

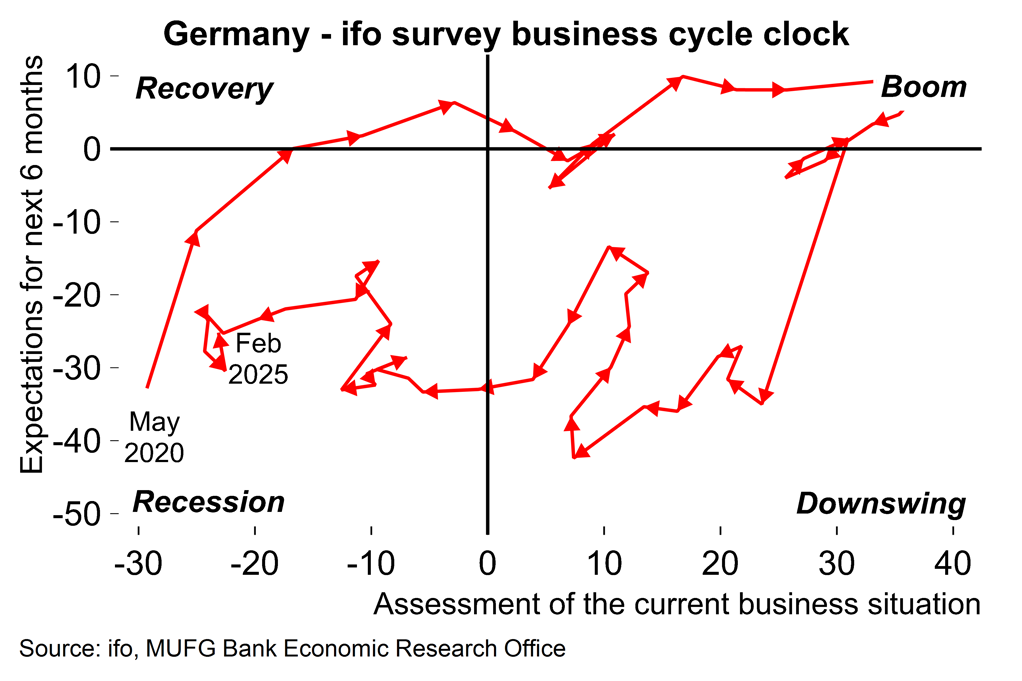

While there are some reasons to question the immediate direct effect of new borrowing on the economy, we would stress that the whole package is a complete sea change in German fiscal policy and we expect to see a strong positive reaction in upcoming business surveys. That could be reinforced in coming weeks if the new coalition can agree on the corporate tax cuts outlined in the CDU/CSU pre-election programme. We judge that the overall confidence effect could support a boost of around 0.1-0.2pp to our 2025 GDP forecast of 0.4%.

We emphasise that there are still a lot of uncertainties around the scope and timing of the new government spending, but our initial estimate is that there could be a boost of 0.8pp to annual average growth in 2026 from the shift in fiscal policy, which would take the rate to around 2%. That figure that would not have seemed credible last month with the economy mired in stagnation.

German business sentiment remains weak, but that is set to change

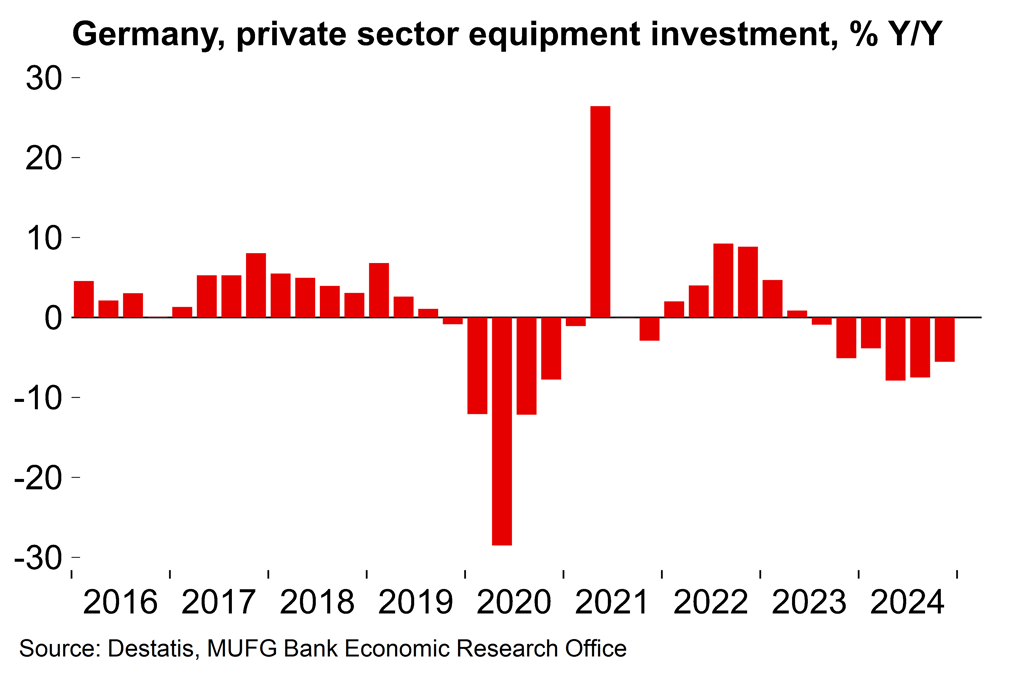

There is plenty of scope for private investment to rebound

Taking a longer view, a big dose of military Keynesianism could be exactly what Germany needs to escape its industrial torpor. We wrote at the start of last year (here) that that it was hard to make the case for a meaningful turnaround in German manufacturing output given long-term structural issues, and there was little sign of any improvement since then. Now, there is plenty of scope for meaningful and enduring growth. If used effectively, infrastructure investment is likely to be productivity-enhancing (there is a lot of low hanging fruit after years of underinvestment). The multipliers involved with defence spending are also likely to improve over time through technology diffusion, e.g. in drones & battery tech, to other industries. We also see potential for crowding-in of private investment following this paradigm shift in German fiscal policy. Immediate risks around the outlook, which were dominated by the possibility of tariffs, are now suddenly a lot more balanced – and tilted to the upside over the medium-term.

What does it mean for the ECB?

The ECB cut again yesterday, as expected, taking the deposit rate to 2.5%. The key line in the statement is that “monetary policy is becoming meaningfully less restrictive” which Lagarde acknowledged was a change which “had a certain meaning”. This provided a mildly hawkish note and bolstered the sense that policymakers are possibly laying the groundwork for a pause to the current sequence of consecutive rate cuts.

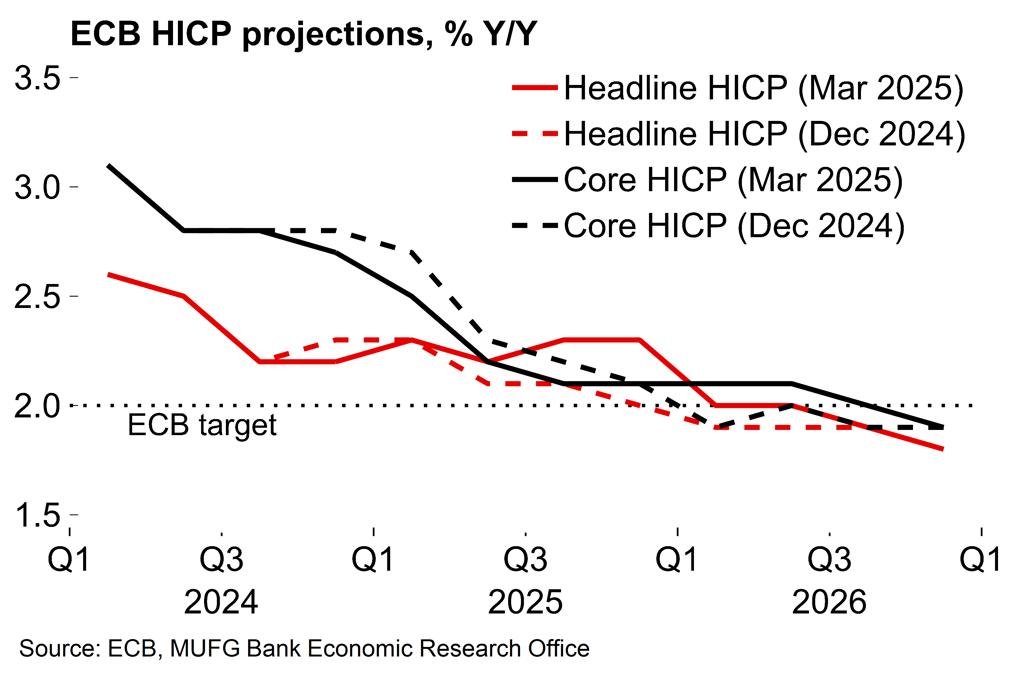

There were updated ECB staff macro projections yesterday (here) but these are essentially redundant after the German fiscal policy announcement so we won’t dwell on them beyond noting that there were mostly downward revisions to growth and inflation (which may otherwise have taken on more significance). At this stage, Lagarde acknowledged that the shift in Germany would have “an impact on demand” but the ECB will not be explicit about that until the package has actually been passed in the Bundestag and more details are known. As it stands, the ECB is sounding increasingly confident about the disinflation process, but medium-term risks have clearly shifted now.

The ECB lowered its inflation projections before the German announcement

There is a consensus that the neutral rate is around 2%

It’s possible that there could be a pause at the next meeting (17 April) by which time there will be more clarity on those fiscal plans. There may also be some more clarity on US trade policy (although uncertainty there will be a permanent feature under a Trump presidency). Given those opposing risks for demand the ECB will want to retain plenty of flexibility. Next week Lagarde will speak at the annual ECB Watchers Conference but it seems unlikely that policymakers will want to provide much of a steer against the backdrop of diverse risks.

In terms of terminal rates, there has been a broad sense for a while, reinforced by the recent ECB post (here), that the neutral rate is around 2%. The ECB continues to sound confident about the disinflation process and, while there may be a pause at upcoming meetings, it seems to have set course to get to that point. However, the chances of rates falling into accommodative territory have now been reduced with any hawkish resistance bolstered by the news out of Germany. Indeed, the huge increase in German investment and the possible productivity boost over the medium-term suggests that risks to neutral rate estimates may lie on the upside.