The UK government announced a surprise-free and sensible Budget which looks to address known issues through supply-side changes. Medium-term challenges will remain, but this was a welcome change after recent policy turbulence.

A better economic outlook allows for more fiscal leeway

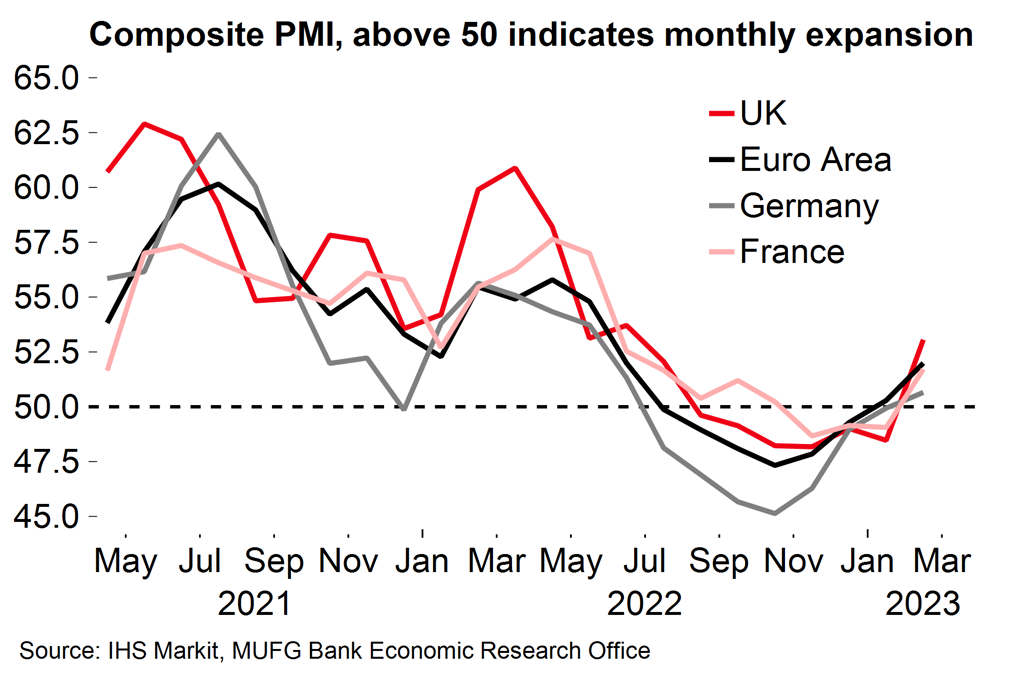

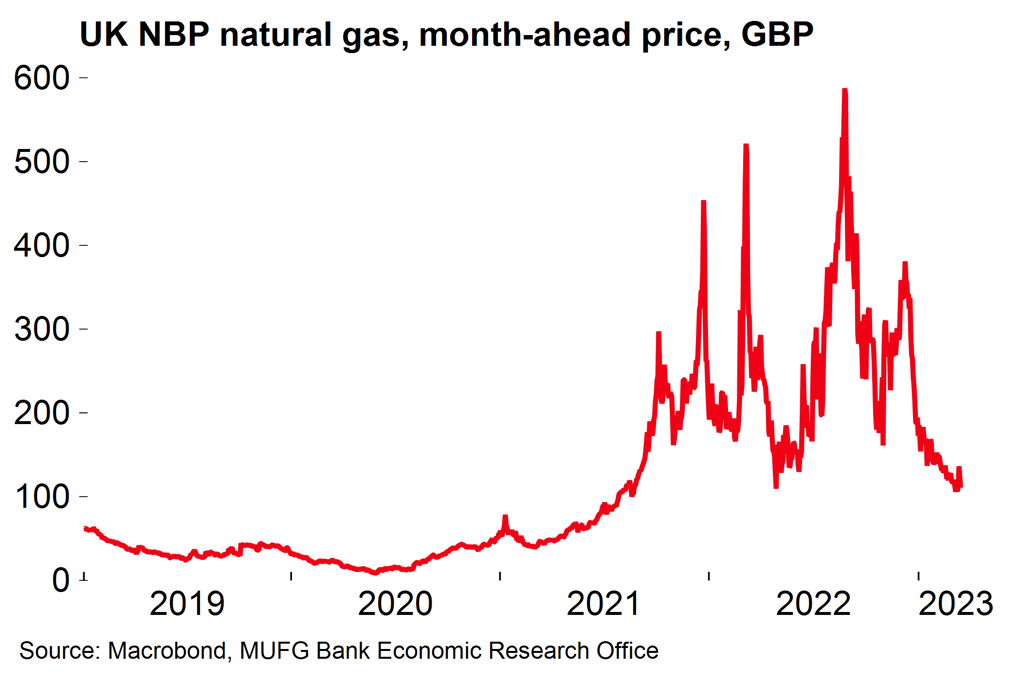

The UK Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, was appointed by previous PM Liz Truss in a last-ditch attempt to find some market support for her agenda. Her successor, Rishi Sunak, has kept him in his post as he looks to continue to restore confidence in the UK economy. Hunt has since benefitted from an improved economic backdrop (Chart 1) with wholesale energy prices falling sharply after his first fiscal announcements in November last year. It’s still not an especially bright outlook for the UK economy (see here) but the worst-case energy-related scenarios have not materialised and a deep recession is likely to be avoided this year.

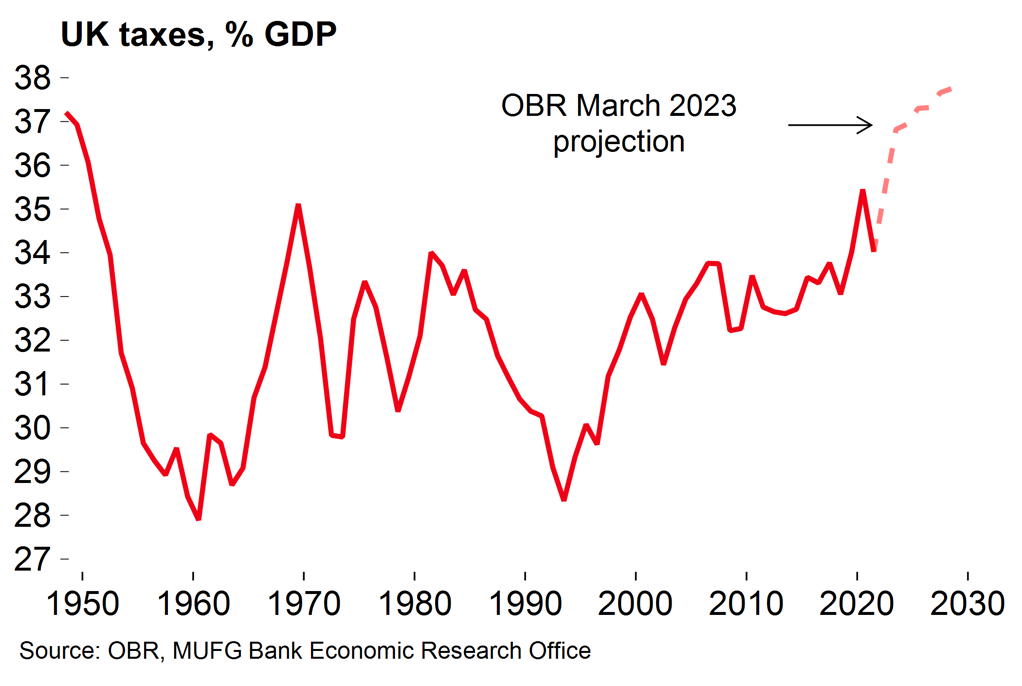

The improved outlook makes the task easier for the government. Better tax receipts (by around 15bn GBP this fiscal year) gives more fiscal leeway for policy decisions. In fact, the painful measures were already announced last year – including significant ‘stealth’ tax increases by freezing tax allowances and bands rather than uprating with inflation, which put the UK’s tax-to-GDP ratio on course to reach historic highs (Chart 2). This meant that the Chancellor was able to announce net fiscal ‘giveaways’ in each of the five forecast years at this week’s Budget, which may have a small positive effect on growth.

CHART 1: ECONOMIC MOMENTUM HAS IMPROVED AS EUROPE WEATHERED THE ENERGY CRISIS

CHART 2: THE UK TAX BURDEN IS STILL SET TO REACH A HISTORIC HIGH

A significant boost for business investment and extended energy support

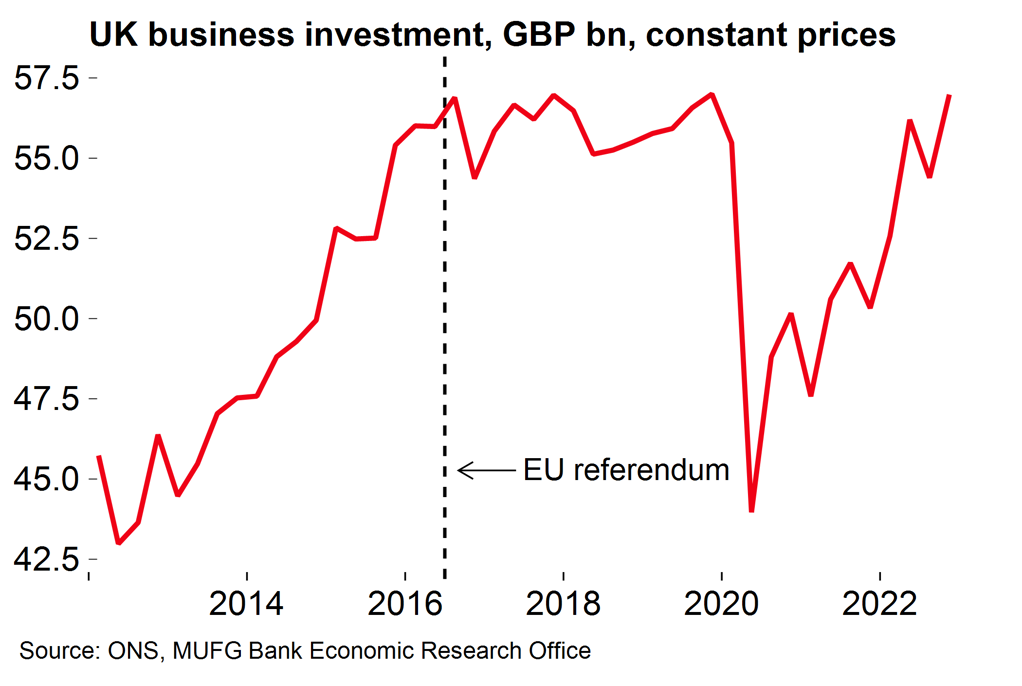

The most significant new measure in terms of expected cost to the government related to business investment, which has been extremely weak in the UK for several years now (Chart 3). Despite this, the corporation tax rate is being increased from 19% to 25% from April, as planned, and the 130% ‘super deduction’ tax break on capital investment will also come to an end. The Chancellor has sought to offset this with a significant new policy of tax relief with “full expensing” for capital investment worth 27bn GBP over the next three years. Firms will be eligible for a reduction in tax of up to 25p on every pound invested until March 2026.

On paper this looks like a good policy, especially if it is made permanent (which is the intention, if fiscal conditions allow). However, as it stands, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) projects that the policy will only serve to bring forward already-planned investment rather than raising the overall level. More broadly, there has been a lot of uncertainty around UK corporate tax policy in recent years. This will remain the case with an election due next year and the opposition party well ahead in the polls. Meanwhile, the attractiveness of the UK as a destination for inward foreign investment is likely to remain diminished after Brexit.

CHART 3: BUSINESS INVESTMENT IS SCARCELY ABOVE 2016 LEVELS

CHART 4: WHOLESALE GAS PRICES HAVE FALLEN SHARPLY SINCE DECEMBER

The Chancellor also announced that energy bill support will be extended to June at the current price level, rather than a 20% increase from April (as had previously been announced). Given developments in wholesale markets (Chart 4) this means a relatively small one-off cost for the government. It now looks likely that energy firms will offer tariffs below the government Energy Price Guarantee level by the summer, so the policy will then become redundant.

Fuel duty will also be frozen at current levels, which includes an extension of the 5p/litre temporary reduction introduced last year when energy prices were rising sharply. Taken together these measures point to a sharper fall in headline than previously expected. The OBR now forecasts that CPI inflation will fall to 2.9% in Q4 this year and remain below the BoE’s target in 2024.

Tackling the UK’s ‘lost worker’ problem

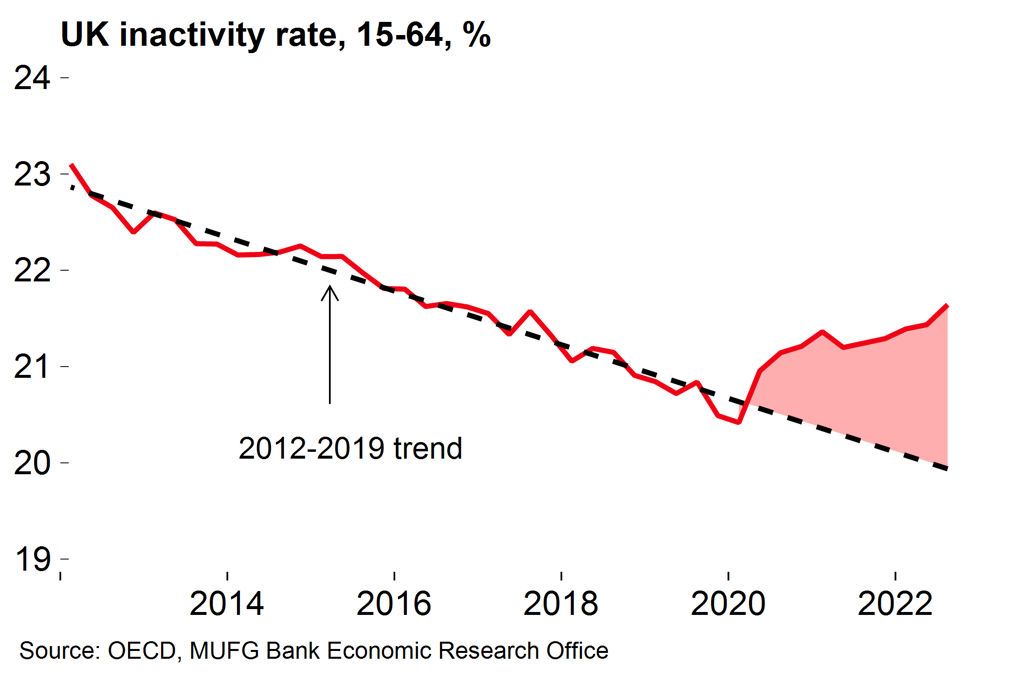

There was a range of measures designed to ‘reactivate’ workers and help with the UK’s labour market inactivity issues (Chart 5). These includes a tweak to pension allowances which might incentivise older workers to delay retirement, and changes to the benefits system for sick and disabled people.

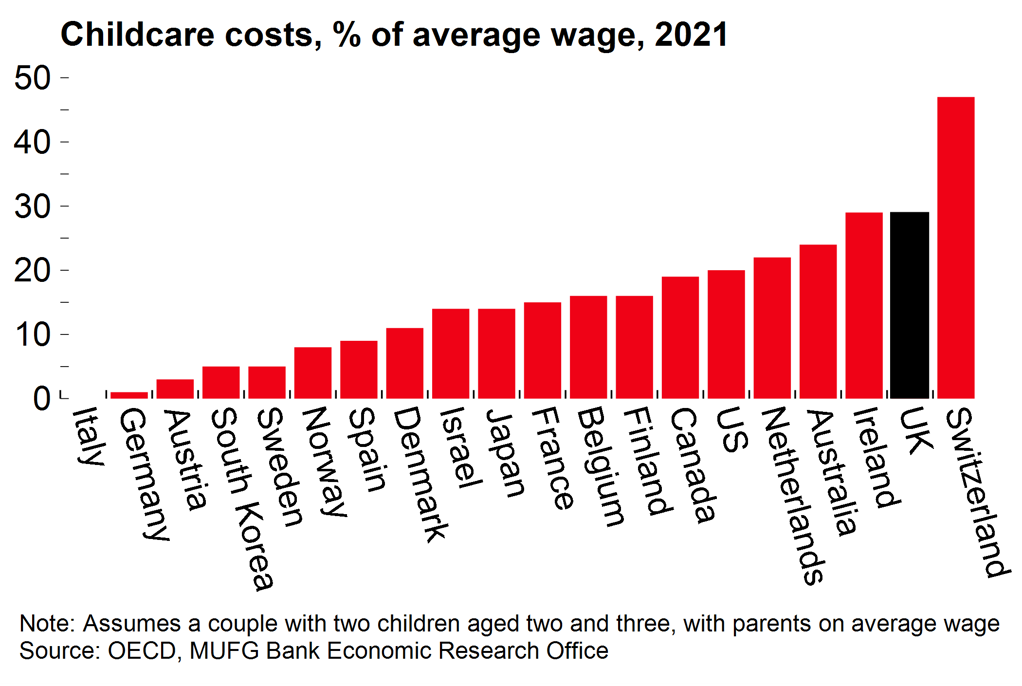

The most significant employment-related policy was a large expansion of childcare funding in a move designed to help more parents stay in work. The UK has high childcare costs (Chart 6). Currently, most families only benefit from government support with childcare once their child turns three years old. This means that there is a big gap between maternity leave (up to a year in the UK) and any state help, discouraging an immediate a return to work. The extra support will only be phased in gradually but could have significant longer-term supply-side benefits.

However, it should be noted that the recent increase in the inactivity rate has mostly been driven by an increase in workers citing long-term sickness. There was no mention of this issue in the Budget announcement. Data points to structural problems with the UK health service – e.g. median wait times for treatment in England have doubled from 7 weeks in 2019 to around 14 weeks – which suggests that this withdrawal of labour due to health issues will continue to weigh on UK potential output over the medium term.

CHART 5: THE UK HAS A 'LOST WORKER' PROBLEM

CHART 6: HIGH CHILDCARE COSTS DETER PARENTS FROM RE-ENTERING THE WORKFORCE

The bottom line is that yesterday’s Budget was a relatively low-key affair with some sensible supply-side changes designed to help with obvious problems (rather than an ideologically-driven policy drive as was the case with the Truss ‘mini-Budget saga – see here). A lot of medium-term challenges will remain, but the new policies are a step in the right direction.

More broadly, it’s clear that the current government doesn’t want to rock the boat too much after years of domestic policy turbulence. There was never much chance of any radical policy announcements, and the market reaction to the Budget was minimal.

Away from fiscal measures, the recent deal between the UK and EU (the ‘Windsor framework’) should be seen in similar light. The agreement, which smooths the implementation of the Northern Ireland Protocol, demonstrates a thawing in cross-Channel relations. PM Sunak has certainly been less antagonistic towards Brussels than his predecessors and this is part of wider efforts to shore up the UK government’s reputation.