- Monthly GDP data showed the UK economy started the year on a weak footing but we continue to expect a moderate expansion in Q1. Underlying macro conditions remain relatively supportive and we see annual growth at 1% this year. While we do expect some loosening of labour market conditions related to higher employer costs from April, we continue to stress that the government’s first budget was ultimately expansionary. Public consumption is set to support overall growth, even if spending plans are pared back slightly.

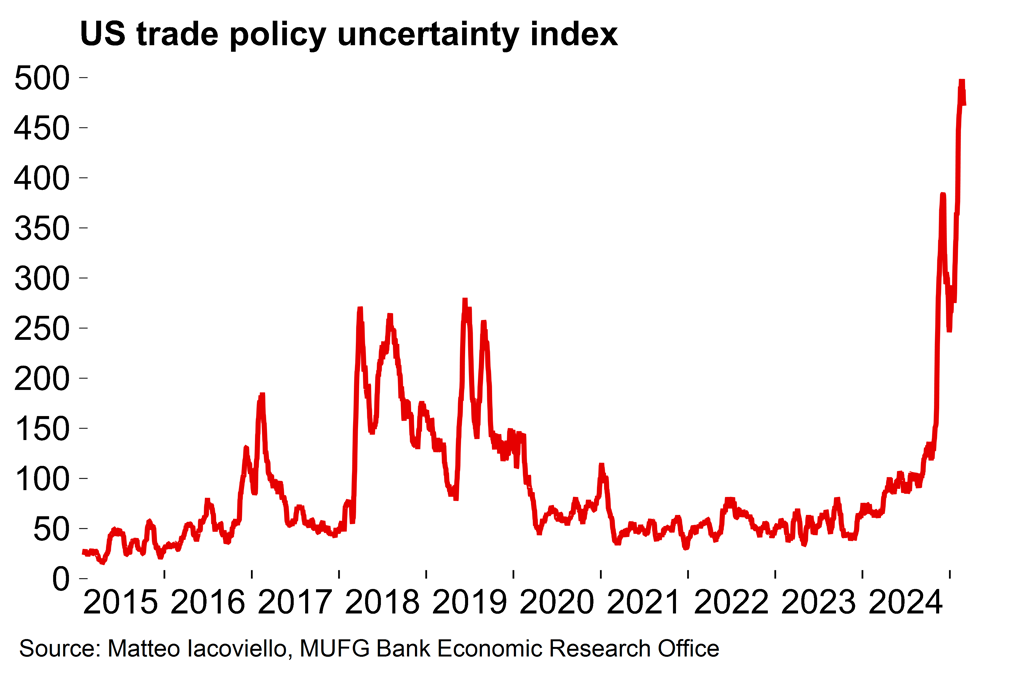

- The government is clearly hoping that the UK will fly under the radar when it comes to Trump tariffs but uncertainty will continue to weigh on business sentiment. External demand conditions could also deteriorate: various warning lights are flashing around the US economy, and the blockbuster German fiscal package may not be sufficient to offset the drag from serious tariff escalation.

- Domestically, the focus remains on UK fiscal policy ahead of next week’s Spring Statement. Higher interest rate costs and slower growth are likely to have entirely eroded the government’s leeway against its (already-loosened) fiscal rules. In response, the government has announced that it will tighten working age benefit eligibility. We expect further measures will be required to restore a meaningful buffer.

- From a growth perspective, it is encouraging that the government is initially looking to trim current rather than capital spending. However, our sense is that the government is kicking the can down the road for now. Another adjustment to the fiscal rules would not be credible and so we judge that there is a clear risk that some tax rises will be required later in the year – even in the absence of a meaningful increase in defence spending.

Look past the noise – UK fundamentals remain broadly supportive for growth

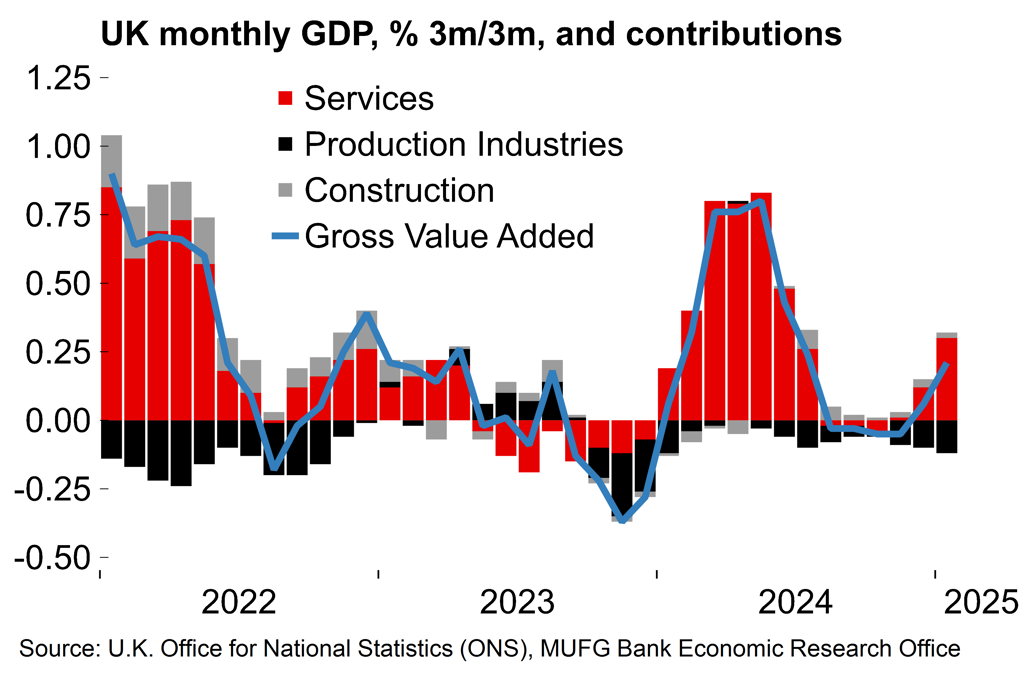

The UK economy started the year on a weak footing with the monthly GDP data for January showing a 0.1% M/M contraction. There was a sharp fall in production (-0.9% M/M) which may have reflected trade policy uncertainty. Poor weather in January (yes, worse than usual) likely dragged on activity as well. As ever, we stress that these monthly GDP numbers are volatile and prone to revision and so caution against reading too much into single figures.

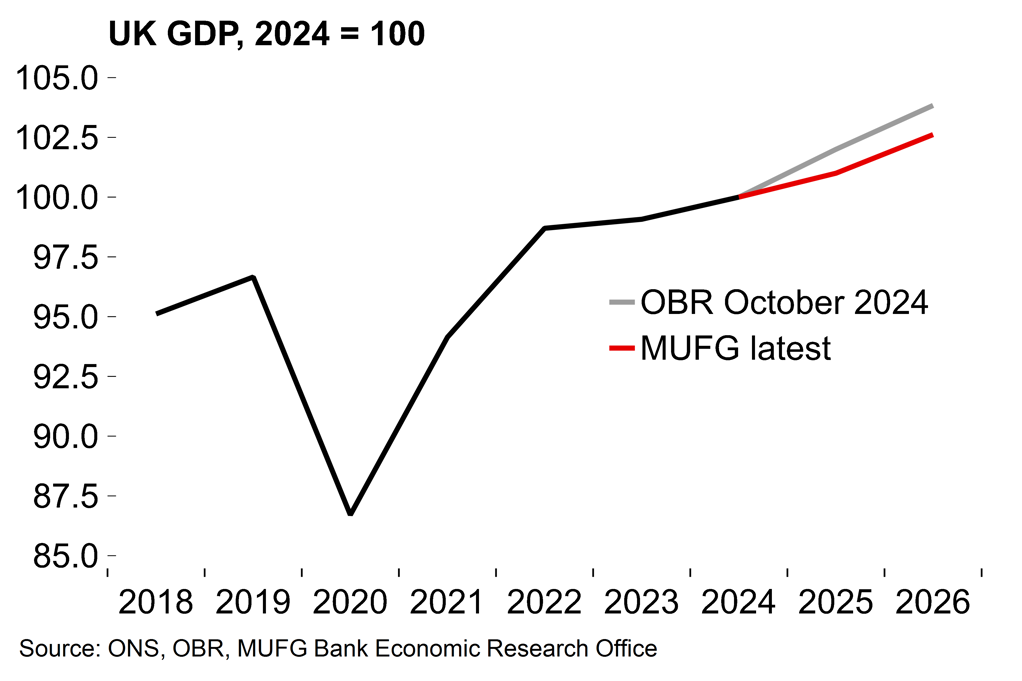

Looking at the broader picture, the contraction in January came after a solid 0.4% M/M expansion in December. That will help Q1 growth, which we are still tracking at 0.3% Q/Q. Stronger momentum in services is also encouraging. We see UK growth at 1.0% this year, a marginal improvement on the 2024 figure, with growth likely to be supported by public consumption. We continue to stress that the government’s autumn budget was ultimately expansionary with a significant amount of front-loaded new spending. As we note below, the government looks set to pare back its spending plans slightly, but the apparent focus on cuts to current rather than capital spending is positive for the growth outlook.

UK growth faded sharply in H2 2024 but the economy has carried some momentum into this year

The last budget was expansionary with significant new borrowing for both current and capital expenditure

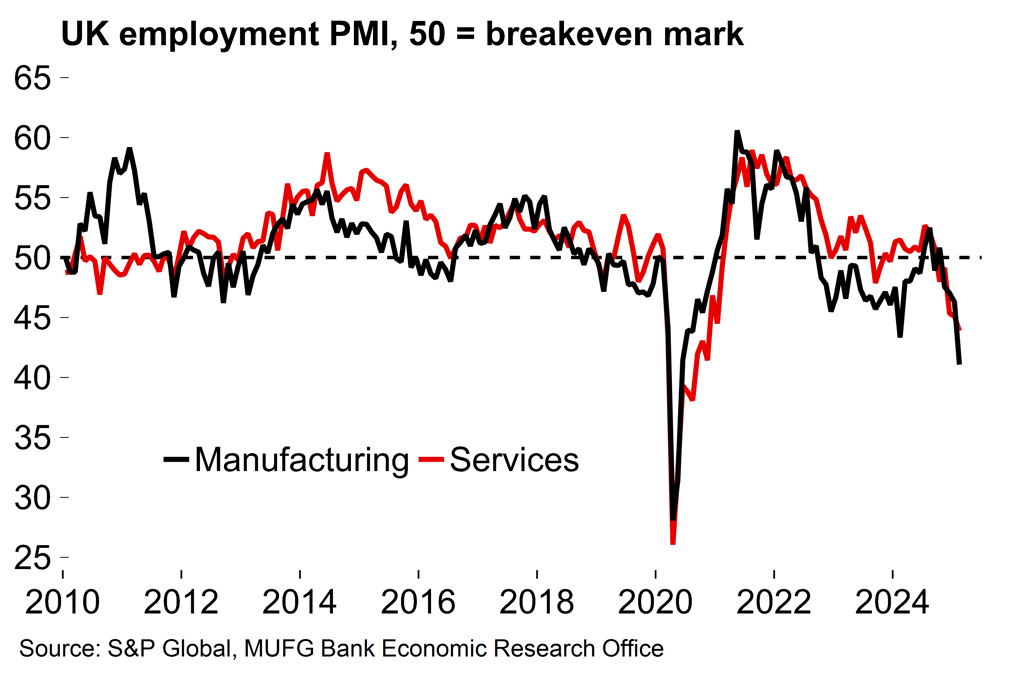

That said, the most significant revenue measure from the last budget – the rise in employer social security contributions – is still a source of uncertainty. That will come into effect from next month. For now, the PAYE employment data remains stable but the composite employment PMI has slumped from above 50 in the summer to just 43.5 last month. Official redundancy notifications to the government (which are required 30-45 days in advance) also seem to be ticking upwards now (see here). This is in line with our expectations for some deterioration of the labour market over coming months.

With the rise in employer costs fast approaching, firms seem cautious about hiring

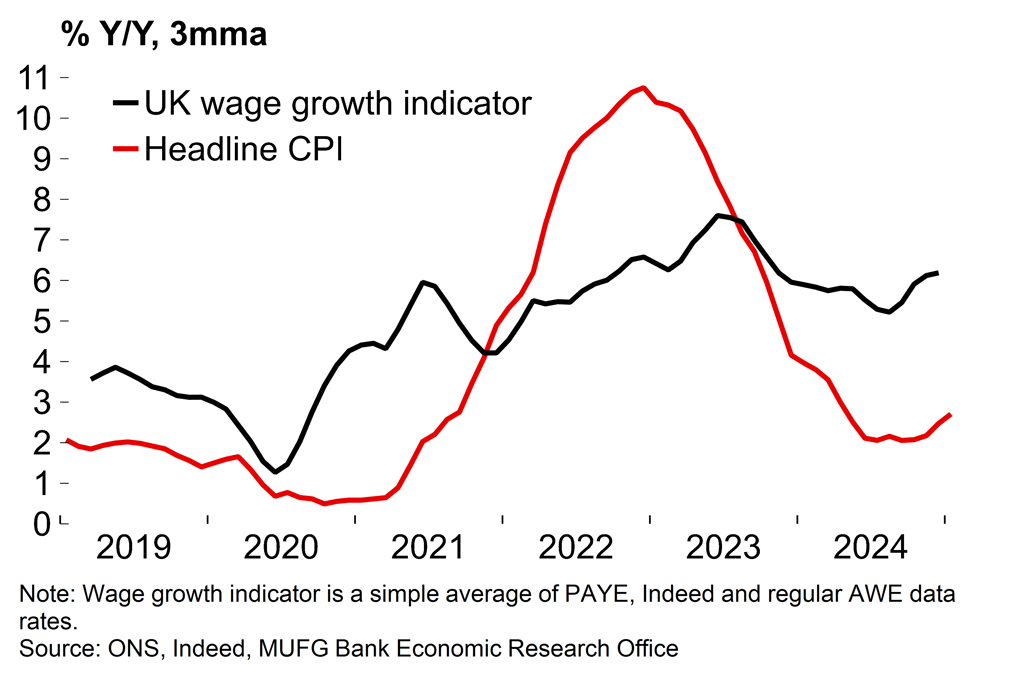

Real wage growth remains firmly in positive territory as pay continues to catch up after the inflation shock

Despite that, real wage growth is firmly in positive territory and is likely to remain so this year. The effect on growth has so far been diluted by the trend towards a higher household saving ratio since the pandemic, but survey evidence suggests the ratio may now be stabilising and we see consumer spending as a steady growth driver this year. At the same time, business investment continues to trend upwards, supported by the BoE’s gradual easing cycle and the still-fading effect of Brexit-related uncertainty.

In short, the macro fundamentals still look reasonably supportive of UK economic growth. But we continue to judge that risks to the UK outlook are tilted to the downside with heightened uncertainty from both external sources (tariffs, global growth) and domestically (predominantly fiscal policy).

The UK may escape Trump’s tariff crosshairs initially, but trade policy remains an obvious risk

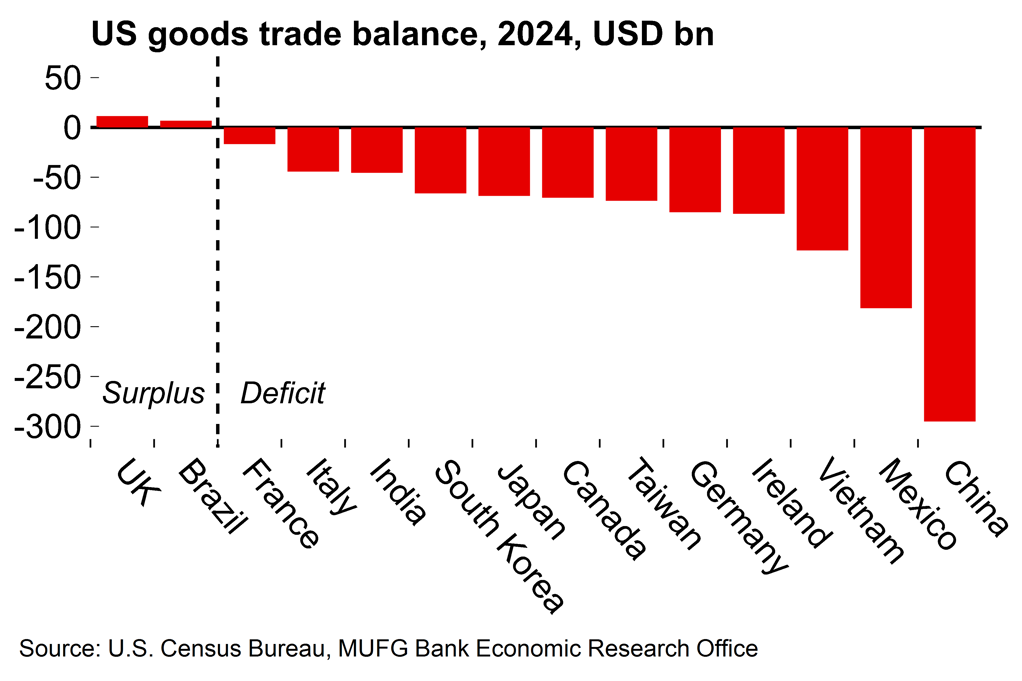

Unlike the EU, the UK government has opted not to retaliate to the imposition of US tariffs of 25% on steel and aluminium. The UK, with relatively high energy costs, has a small steel industry and less than 10% of exports go to the US (~400m GBP annually). The calculation seems to be that it is preferable to avoid escalation given low direct exposure to the measures. The US administration has indicated that it is now looking to impose “reciprocal” tariffs. That would see tariffs match a range of measures (perhaps including VAT, which the US administration apparently sees as similar to a tariff) imposed by other countries, on an individual basis. This is a complicated task and we expect that the US administration would initially focus on trading partners with the largest surpluses vis-à-vis the US.

There is no great goods trade imbalance between the US and the UK (in fact, Census Bureau data suggests that the US may actually have a small surplus with the UK). On that basis, the UK government will hope to keep its head down and escape the Trump administration’s crosshairs. Let’s see if that approach works. Policy volatility will remain a feature of this US presidency and the UK would be especially vulnerable to tariffs on pharmaceutical products (8.8bn GBP total exports to the US in 2023) and autos (6.4bn).

The UK may not be a priority for new US tariffs...

...but trade policy uncertainty is set to remain a drag on growth

Don’t expect much (or any) boost from external demand

The UK would also be exposed to a slowdown in the US economy. The US is the UK’s largest (national) export partner, accounting for 27% of UK services exports and 15% of UK goods exports (see a summary of ONS data here). US consumption growth looks weaker at the start of the year even before any uptick in inflation related to tariffs. At the same time, volatility around trade, immigration and fiscal policy is likely to remain a headwind for fixed investment and employment growth.

Meanwhile, the huge fiscal measures planned in Germany (see here) are set to be mildly supportive for UK growth next year, but we would stress that there are plenty of risks around the euro area outlook over the near term given trade policy uncertainty. As expected, the EU announced targeted countermeasures last week which match the scope of new US tariffs – and Trump then responded by threatening 200% tariffs on US imports of EU alcohol.

The direct effects of any tit-for-tat tariff escalation as well as broader uncertainty around trade policy will weigh on the euro area’s stuttering industrial sector. As noted last autumn (see here), we worry about the risk of second-round effects on the labour market. With difficulties in recruiting appropriately skilled workers, it seems that euro area manufacturing firms have ‘hoarded’ labour and avoided redundancies in the hope that demand conditions will eventually turn around. Trump tariffs could be the trigger for firms to push ahead with lay-offs that could tip the euro area economy into a more serious slowdown – which would be another headwind for UK growth.

Will the UK government row back on its spending plans?

Domestically, UK fiscal policy will remain in sharp focus this year. At its first budget in October, the new government loosened the fiscal rules to allow for significant, front-loaded spending increases (see here). Adherence to the fiscal rules is judged by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK’s independent fiscal watchdog. According to their projections, the government left itself very limited headroom of just 10bn GBP (0.3% of GDP) at the end of the rolling five-year forecast horizon.

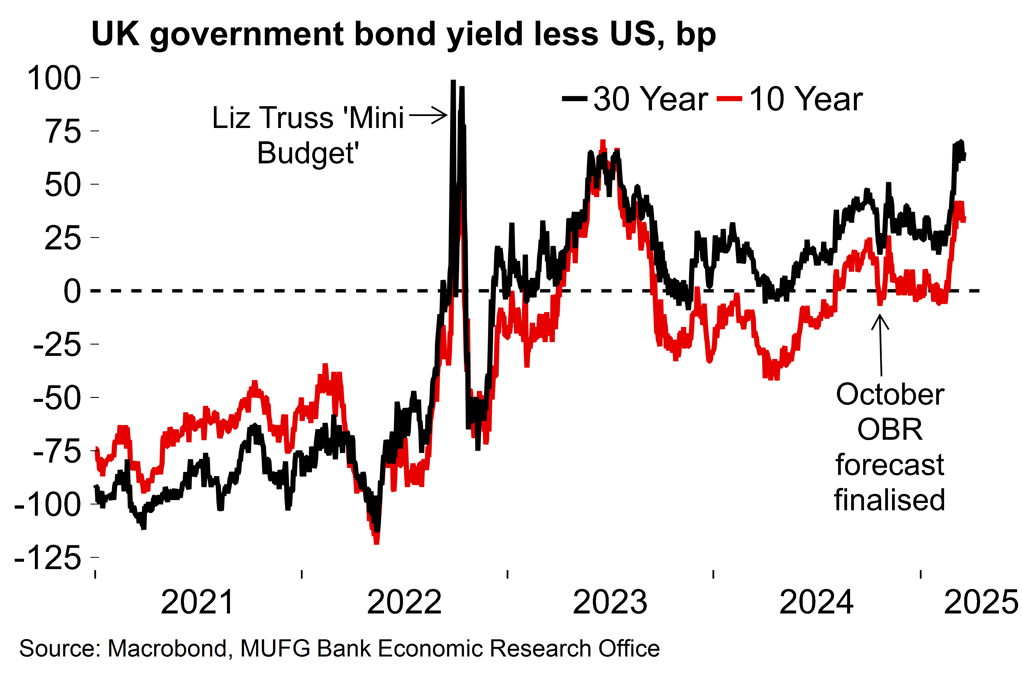

The OBR is legally required to provide two sets of forecasts a year and will publish its updated figures on 26 March alongside the chancellor’s Spring Statement. We expect that these forecasts will show that the government’s wafer-thin headroom against its own fiscal rules has been erased entirely by lower receipts (as noted at the time, the OBR’s growth forecasts were certainly on the optimistic side) and higher interest costs since the Autumn Budget.

New borrowing costs have risen since the budget

The OBR’s last growth forecasts look optimistic

After last year’s election the government stated that it is “is committed to one major fiscal event a year” to support economic stability – and so ideally it would avoid any changes at the stage. But the chancellor is now expected to prove her adherence to the fiscal rules in order to retain market credibility. Gilt yields rose markedly at the start of the year in response to weaker UK growth and concerns that policy rates would remain higher for longer than expected.

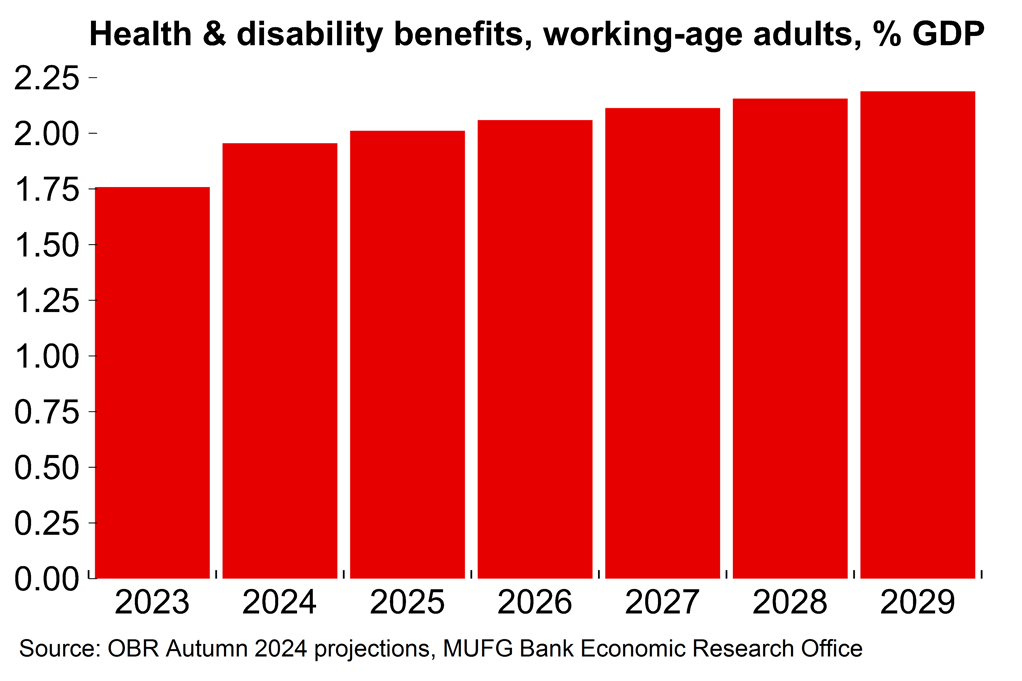

The government seems to have focused initially on health-related benefits (where the government spends 75bn GBP annually). Of that, 56bn is spent on working age adults (1.7% of GDP) and that is set to rise over coming years. The work and pensions secretary has already announced some changes to working age benefit eligibility, which she hopes will save 5bn by 2029. This alone does not look sufficient to restore any useful buffer against the fiscal rules and the government will likely make further fiscal adjustments at the Spring Statement.

From a growth perspective, it is positive that the government is looking to trim current rather than capital expenditure. Infrastructure investment generally has good fiscal multipliers – it cannot be saved and has to be spent domestically. Politically, though, it can be easier to cut public capex plans given the benefits may not be obvious for years, or even decades. For reference, the OBR’s estimates of year-ahead fiscal multipliers are 0.83 for public investment and 0.57 for welfare (see here).

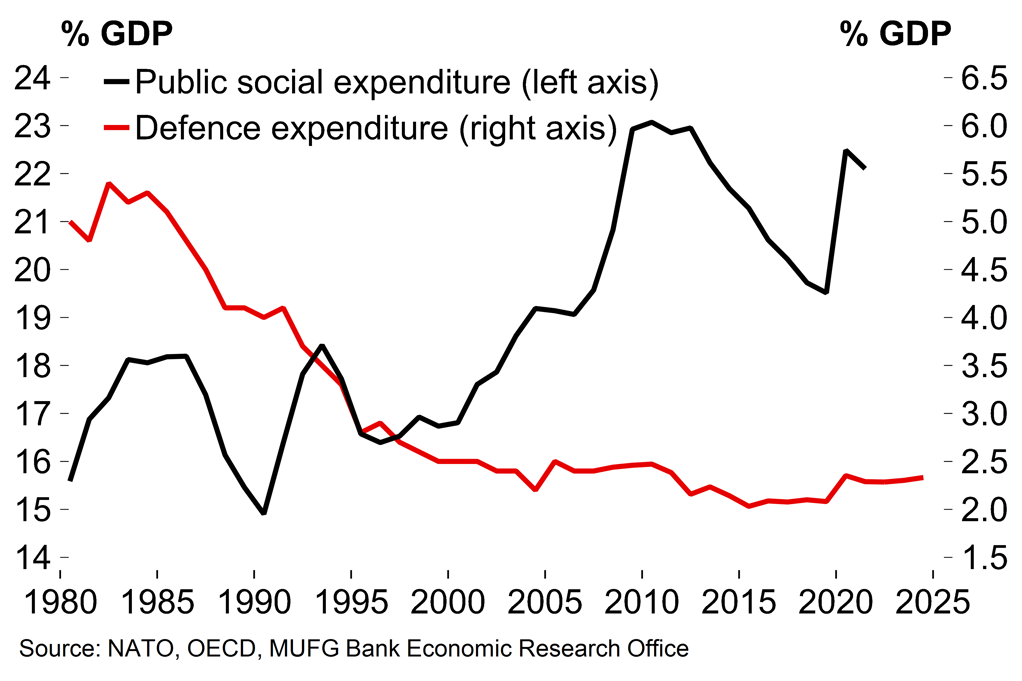

Taking a wider view, a move to trim health-related benefit expenditure would fit into the wider debate about the ‘peace dividend’ in Europe. As defence spending fell as a share of GDP from the 1980s, welfare spending generally increased across the continent. The UK government has stated its initial aim is to increase defence spending from 2.3% in 2024 to 2.5% of GDP by 2027, funded directly by reducing the overseas aid budget. To our minds, this is clearly insufficient given the range of threats facing the UK and we suspect that the government will be forced to go further (i.e. at least 3% of GDP). That will require politically difficult trade-offs.

The UK’s working age benefit costs are set to increase over coming years

The ‘peace dividend’? Social spending increased as defence was pared back

Tax rises may still be inevitable

Even in the absence of more meaningful defence pledges, our view is that the government will be forced to increase taxes at some point during this parliament. The reality is that market developments and slower growth have left the government with very limited leeway against its already-loosened fiscal rules. Moving the goalposts by tinkering with these rules again would clearly be damaging for credibility and likely result in counterproductively higher borrowing costs

Against that background, we see tax rises in the next autumn budget as fairly likely at this point. This would be a huge challenge in terms of official communication. The government bungled the messaging around its first budget by announcing months in advance that there would be ‘painful’ measures, without providing any guidance about where the axe might fall. Unsurprisingly, that encouraged speculation which weighed heavily on sentiment indicators and contributed to the UK economy losing momentum sharply in H2 2024.

As it was, the ‘pain’ was mostly in the form of increased employer social security contributions from April this year (which we discuss above). That was a function of the government’s pre-election commitment not to raise income tax, employee national insurance, VAT or corporation tax, which together provide the bulk of government tax take. This pledge meant that the previous government’s 2pp National Insurance cut last March – essentially a pre-election giveaway – couldn’t simply be overturned. That cut reduced the tax take by around 10bn a year and came on the back of a similar cut the previous year. Reversing these would immediately restore the government’s headroom against its fiscal rules, but would mean backtracking on the pre-election pledges.

The government may instead opt to go along the well-trodden ‘stealth’ route by leaving income tax thresholds frozen (rather than uprated with inflation) beyond 2028, which is the current plan. Another option the government might consider is specific, separate packaging for a small tax rise – something along the lines of the Health and Social Care Levy (see here).

To leave a greater margin of leeway, or to increase defence spending meaningfully, would require more decisive action. Real game changers would require shifts along the lines of higher income tax rates on median earners, say, or watering down the triple lock (which uprates the state pension by the highest of inflation, earnings growth or 2.5%). Of course, such moves would be fraught with political risk, to put it mildly, but also economic risk if the messaging were to be handled badly and cause a confidence shock.

In short, there are no easy options for the government. The UK simply does not have the fiscal space to implement the sort of blockbuster fiscal stimulus announced in Germany (see here). Indeed, the government may be forced to backtrack on its (much more modest spending) plans which were announced only last October, at least to a limited extent. As ever, the gilt market will be the ultimate arbiter of whether it goes far enough, but our view is that the need for trade-offs is only likely to increase on the back of greater defence requirements. For now, it seems that the can is being kicked down the road on that and we don’t expect fireworks at next week’s Spring Statement announcement. However, tweaks to previous spending plans will still give some indication of the government’s intentions around its wider strategy.