Europe Weekly Focus

- Apr 12, 2024

- The ECB remains on course for an initial rate cut at its next meeting in June after laying some more groundwork for easing yesterday. That said, policymakers’ preference for short-term guidance only is likely to have been reinforced by inflation developments in the US. While the ECB seems comfortable with making the first step alone it will likely be hard to ignore what the Fed does further down the line.

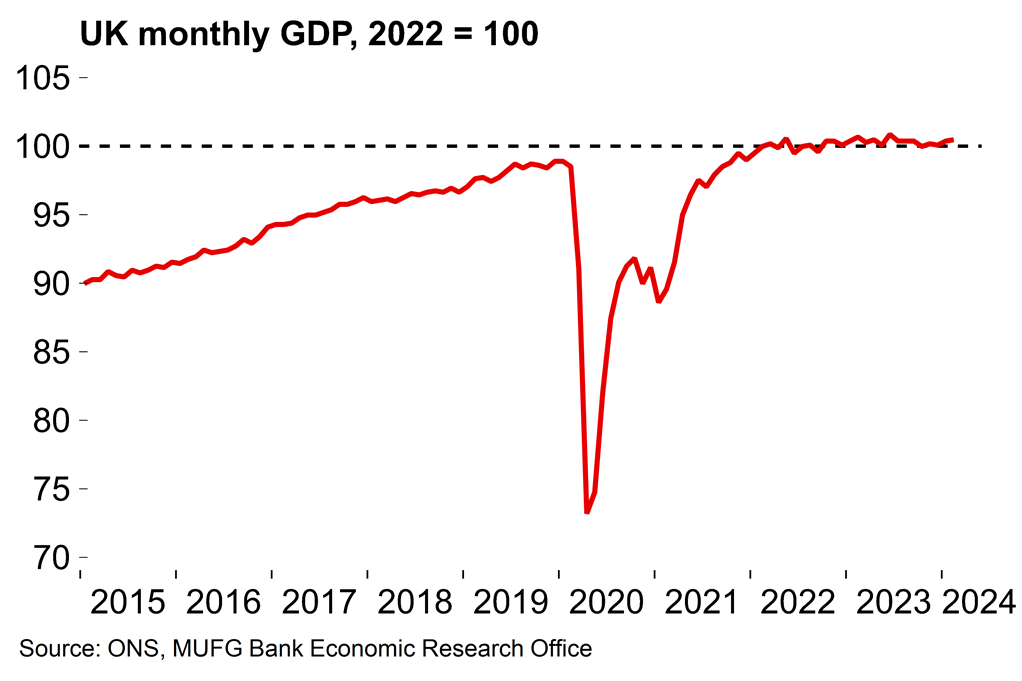

- Monthly data has essentially confirmed that the UK economy is no longer in recession. The economy started the year on firmer footing and we are now tracking Q1 GDP growth at 0.3% Q/Q. After a prolonged period of stagnation, the ingredients are there for moderate growth to continue over coming quarters.

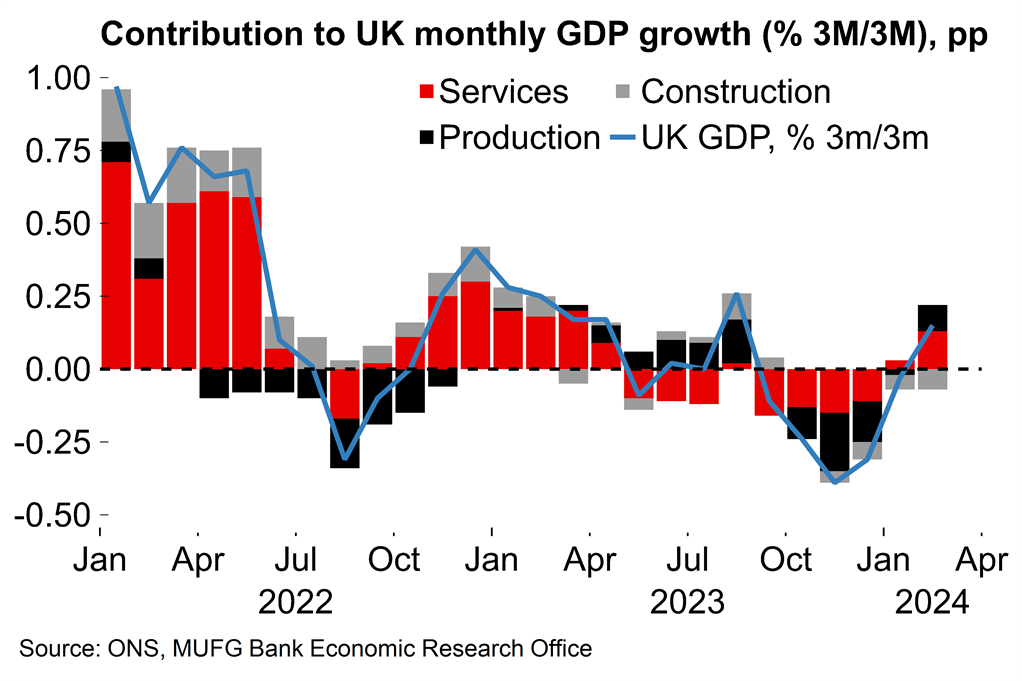

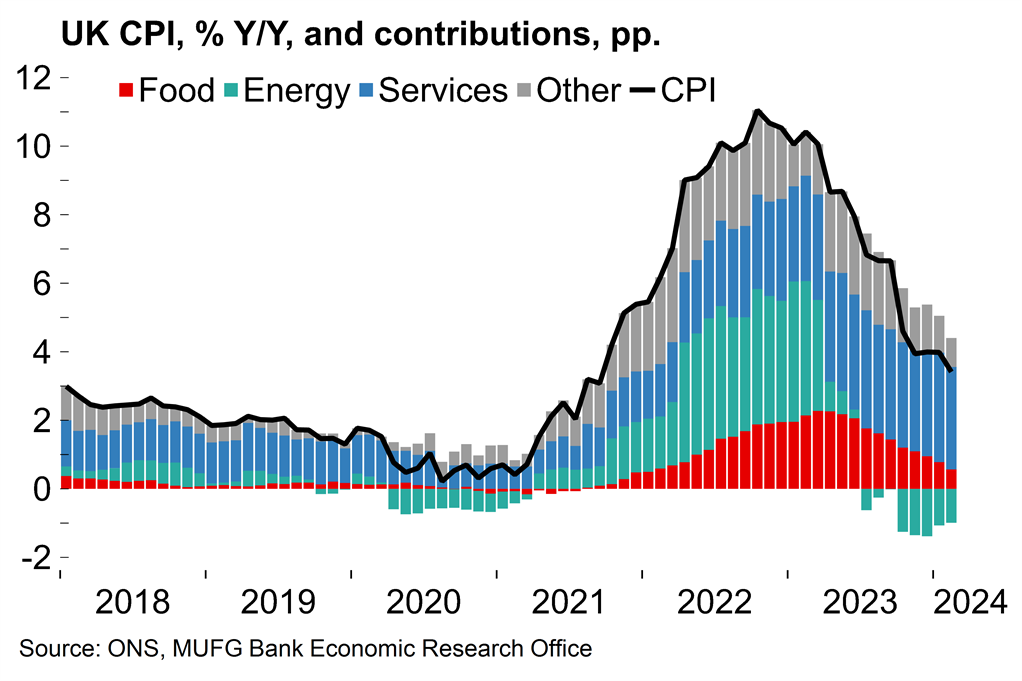

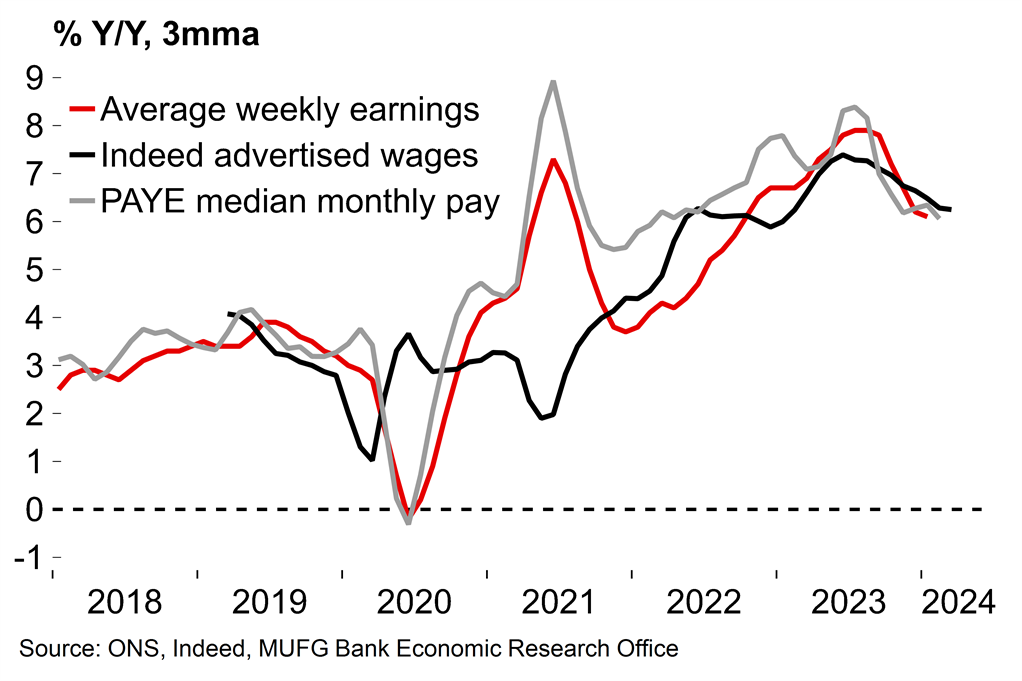

- Next week will see a range of UK data releases which includes wage growth and CPI. We expect to see more evidence that the disinflation process remains on track in the UK. There will also be euro area industrial production figures for February. National data for Germany surprised on the upside this week which suggests that the German economy may have returned to growth in Q1.

ECB review – Still on course for June

The ECB left rates unchanged – probably for the last time in this cycle. After seemingly steering expectations towards June for the first rate cut in recent months, policymakers continued to set the stage for easing at the next meeting. The updated statement highlighted that policy is restrictive and now making a “substantial contribution to the ongoing disinflation process”. This was emphasised in this week’s ECB Bank Lending Survey (here) which noted that firms’ “demand for loans continued to decline substantially” – and that was mainly driven by the effect of higher interest rates.

Significantly, the statement also noted that “it would be appropriate to reduce the current level of monetary policy restriction” if updated projections, which are released at the next meeting, were to reflect increased “confidence that inflation is converging to the target in a sustained manner”. In the press conference, Lagarde conceded that a few governors “felt sufficiently confident” to start easing now on the basis of recent data – but the majority wanted to “reinforce confidence” with more data in June.

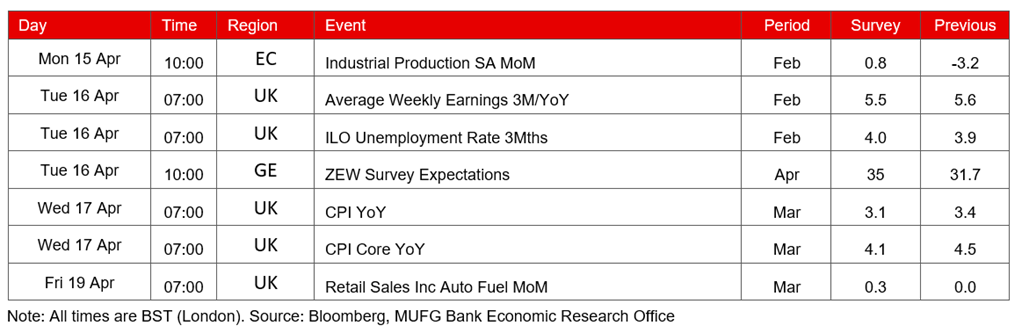

We’d also noted previously that the ongoing stickiness of services inflation is concerning with the component steadfastly remaining at exactly 4.0% Y/Y for five straight months ago. Services contributed 1.8pp to the headline rate of 2.4% in March, and, on a three-month annualised basis, the rate rose again suggesting ongoing momentum (Chart 1). Lagarde seemed happy to look past still-high services inflation: “we are not going to wait until everything goes back to 2%” she said, noting that it was inevitable that some components could show slightly higher annual rates.

So, in the absence of a significant data shock, June remains very much on for the first cut. The key question relates to the subsequent path for rate cuts. In the statement it was noted that “the Governing Council…is not pre-committing to a particular rate path”. This is not new: Lagarde stressed that “even after the first rate cut, we cannot pre-commit to a particular rate path” in her ECB Watchers speech last month (here). But the ECB’s preference for short-term guidance is only likely to have been reinforced by inflation developments in the US which seem to have reduced the chances of imminent Fed rate cuts.

There was some push-back on this – Lagarde said “we are not Fed dependent” and said that it should not be assumed that what happens in the euro area “will be the mirror” of what happens in the US. She also noted that “the nature of inflation in the euro area was different to the nature of inflation in the US” – alluding to the idea that price growth across the Atlantic has been much more demand-driven and perhaps fuelled by expansive government spending. However, Lagarde did concede that developments in the US could find their way into the next batch of the ECB projections. Indeed, as the ECB’s chief economist noted last year during the tightening cycle, the exchange rate is “a material driver of economic activity and inflation through a range of channels” (see here).

Chart 1: Signs of increased momentum in services inflation

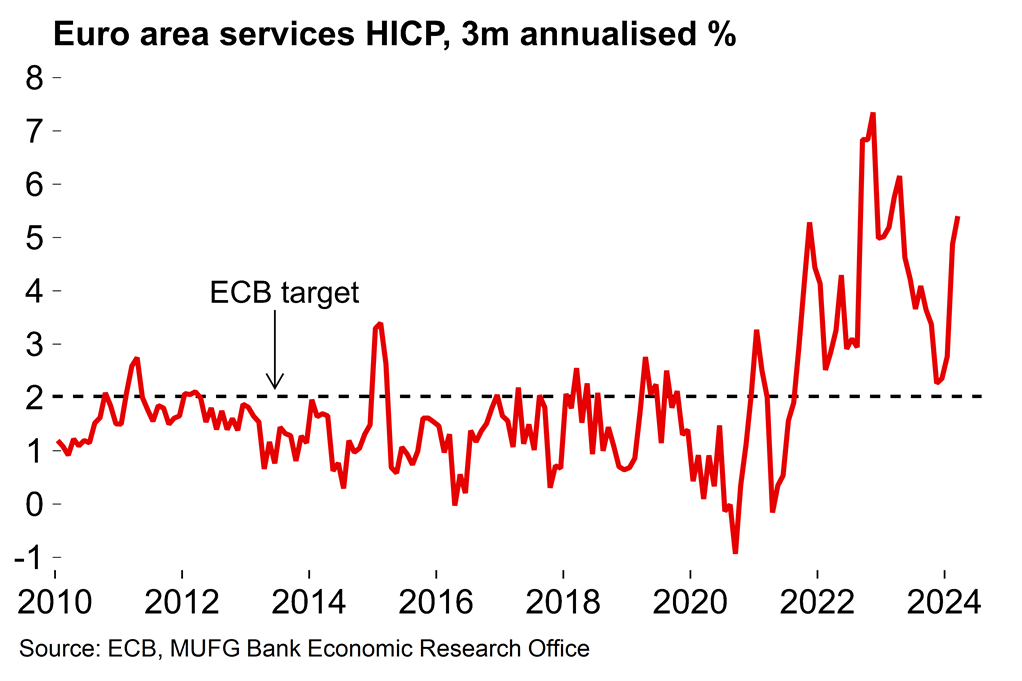

Chart 2: Markets have priced in over three cuts this year

Market participants are currently pricing in slightly over three ECB rate cuts in 2024 (Chart 2). Our long-standing forecast is for four cuts in 2024 – at the start of this year that was decidedly hawkish (see here), but is now on the dovish side of market pricing. We are confident that domestic inflation pressures will continue to ease through the rest of the year in the euro area. However, developments across the Atlantic cannot be ignored – euro weakness as a recent of divergence in rate expectations would have a positive effect on euro area inflation through higher import prices. The most immediate channel is through commodities priced in dollars – and a weaker euro would exacerbate the recent upward pressure on energy prices from moves in oil markets (although it should be noted that European gas price developments remain more benign).

While the ECB was late to the party, ultimately there was a degree of synchronisation in the pace of tightening between major central banks during the Fed-led 2022-23 hiking cycle. The timing of the initial move may vary but we’d expect something of a similar pattern on the way down. The ECB seems comfortable with making the first step alone, but further down the line it will be hard to ignore what the Fed does.

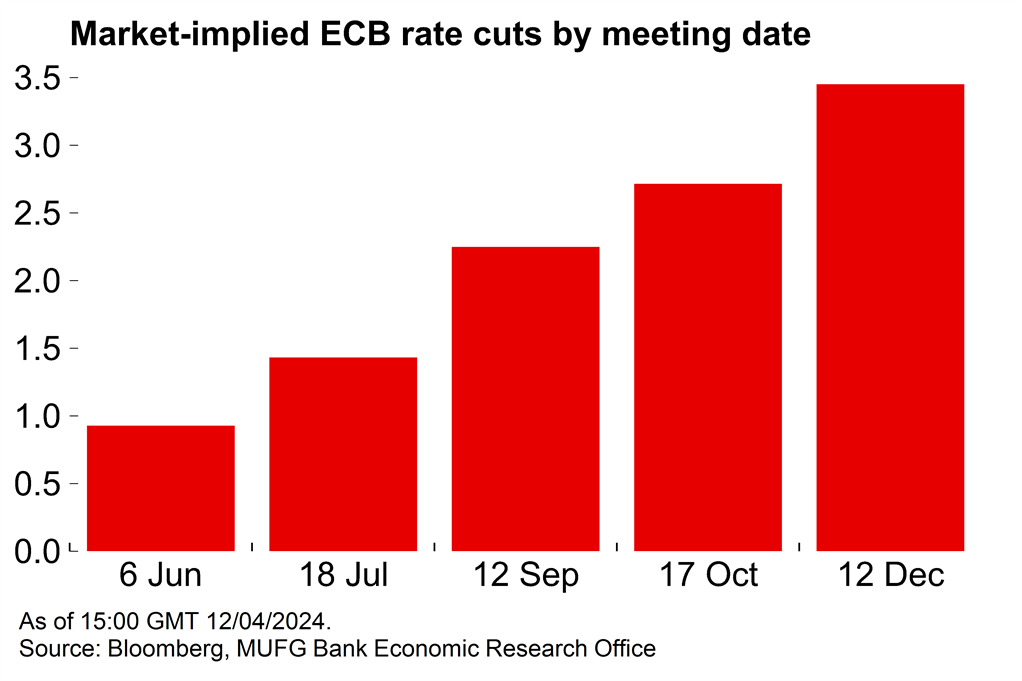

The UK recession was mild and short-lived

The monthly UK GDP release for February has essentially confirmed that the UK economy is no longer in recession. The economy grew by 0.1% M/M, following 0.3% growth in January (which was revised up from the initial estimate of 0.2%). Output would need to have plunged by 1.3% M/M or more in March for there to be another quarterly GDP contraction. We can safely say that didn’t happen and hence that the H2 2023 technical recession was mild and short-lived, with the economy shrinking by just 0.4% across the two quarters.

While the headline was encouraging, the details were somewhat mixed. Manufacturing output rose by 1.2% M/M. Vehicle production was notably strong (3.7%), growth was broad-based across most sub-sectors. This came in contrast to the evidence from survey data (the UK manufacturing output PMI was loitering below the breakeven mark in February at 48.3). On the other hand, construction output fell by 1.9% M/M. That was likely weather-related: the south of England experienced the wettest February since records began in 1836. Rainy weather likely weighed on the services sector too, with growth of just 0.1%. Consumer-facing services continue to tread water, down 0.1% M/M and still 5.7% below the pre-pandemic level.

Zooming out, stronger growth at the start of 2024 comes after a prolonged period of stagnation (Chart 4). Output was 0.2% lower than the February 2023 level – and only 0.5% above the February 2022 mark. The UK economy has essentially drifted sideways as monetary policy tightening and squeezed household finances have weighed on activity. It is still too early to definitively say that the economy has turned a corner, but today’s data shows that it has certainly started the year on a firmer footing and the ingredients are there for moderate expansion through the rest of the year. In particular, the ongoing recovery in households’ real purchasing power as inflation fades should see consumer spending become a more reliable growth engine.

Chart 3: The UK economy has returned to growth

Chart 4: The broader picture remains one of stagnation

However, while our base case for the UK economy is a consumer-led recovery this year, there is a risk that sentiment, both for consumers and businesses, could be punctured somewhat if the BoE fails to deliver the expected degree of easing.

In isolation we continue to judge that UK interest cuts would be appropriate by the summer given ongoing signs of cooling wage growth. We expect more evidence next week on that front (see below). And, despite the better news on GDP today we see only moderate growth ahead – not enough to derail the UK disinflation process. Nonetheless, concerns about divergence with the Fed after clear evidence of persistent inflation pressures across the Atlantic will be pertinent for at least some MPC members. For firms and households, a sense that interest rates will remain high for longer would likely pass through to confidence indicators – the UK PMI release has noted that optimism is, at least in part, linked to “lower borrowing costs”. Market participants are currently pricing in around 55bp of BoE cuts this year – which is down from around 160bp at the start of 2024.

Next week – UK wage and CPI data in focus

The BoE will be closely watching a range of key UK data next week. The official measure of pay growth is likely to continue to ease amid broader signs of ongoing weakening in the labour market, but will likely remain above 5.5% (in isolation still uncomfortably high from a monetary policy perspective, but it is a lagging indicator and is moving in the right direction). Headline UK CPI inflation probably also moved slightly lower in March, with a more significant drop to come in April after the fall in the household energy price cap this month. Policymakers will pay particular attention to the services component which has remained above 6% since the start of 2023.

Chart 5: The UK disinflation process continues – but services inflation remains persistently elevated

Chart 6: There are signs that UK pay pressures have started to ease

March UK retail sales figures will also be released. The wet February weather which weighed on GDP continued into March – England and Wales recorded over 150% of their long-term average rainfall for the month – and that may have weighed on consumer spending.

Next week will also see the release of aggregate euro area industrial production for February. Available national data points to a moderate expansion. Of those numbers, the German figure was most notable. It showed that production increased 2.1% M/M, with January growth also revised up, from 1.0 to 1.3% M/M. These better production numbers combined with improving soft data can be taken as a tentative sign that German’s industry may be starting to experience something of a cyclical recovery after a prolonged slump. The more structural issues – e.g. higher energy costs, competition from China in the automobile space – are set to remain. But the numbers do support our expectation that the German economy as a whole will return to growth in Q1 after the 0.3% Q/Q contraction recorded at the end of last year. A moderate expansion through the year as real incomes recover remains our base case for Germany.

Key data releases and events (week commencing Monday 15 April)